It might surprise you that the Briscoe Center’s collections are not only global in their reach—they are, literally, astronomical. In this episode, we will explore outer space through the art of quilts.

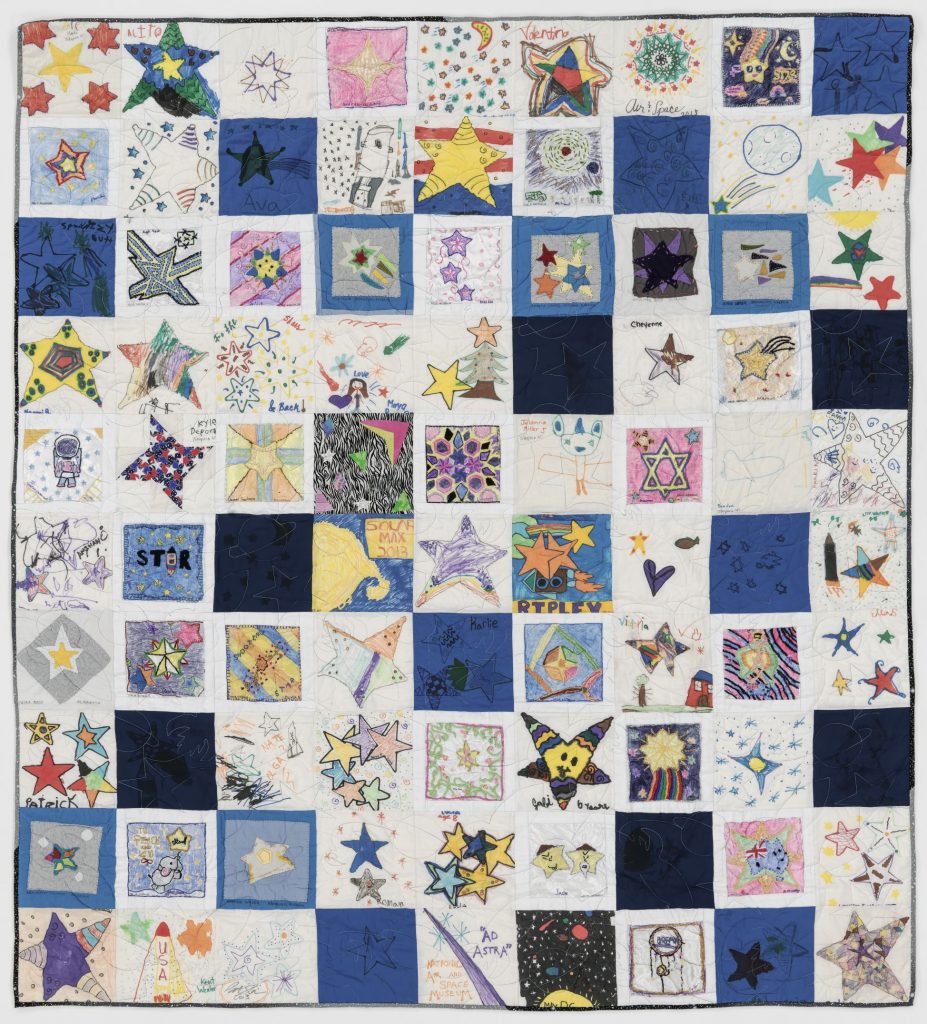

While living on the International Space Station in 2013, astronaut (and UT alum) Karen Nyberg stitched a nine-inch, star-themed quilt block. She and NASA invited crafters and artists to help create a global quilt, inspired by the stars. Nyberg’s single quilt block sparked a worldwide project that resulted in the submission of 2,400 quilt squares to NASA, many accompanied by letters and stories of the inspiration provided by outer space. A team of NASA and Johnson Space Center volunteers quilted the squares together, resulting in twenty-eight king-sized quilts.

Briscoe Center Associate Director Sarah Sonner speaks to astronaut Karen Nyberg about the unique challenges of sewing in space, as well as the connection between mechanical engineering and quilting. Sarah also discusses the Astronomical Quilts! project with Bob Ruggiero and Vicki Mangum, longtime staff members of Quilts, Inc. and key figures in the Astronomical Quilts! project on the ground, which involved coordinating submissions and volunteers to make twenty-eight quilts that are out of this world!

These discussions show how historical evidence can be found in many places—even in orbit around the earth.

For more information about Dr. Karen Nyberg and her work please visit: https://karennyberg.com/

For more information about the International Quilt Festival, the Texas Quilt Museum, or quilting in general, please visit: https://www.quilts.com/

Center: Karen Nyberg studies a quilt from the Astronomical Quilts! Block Challenge Collection, 2016-316-01 during her visit to the Briscoe Center in 2020.

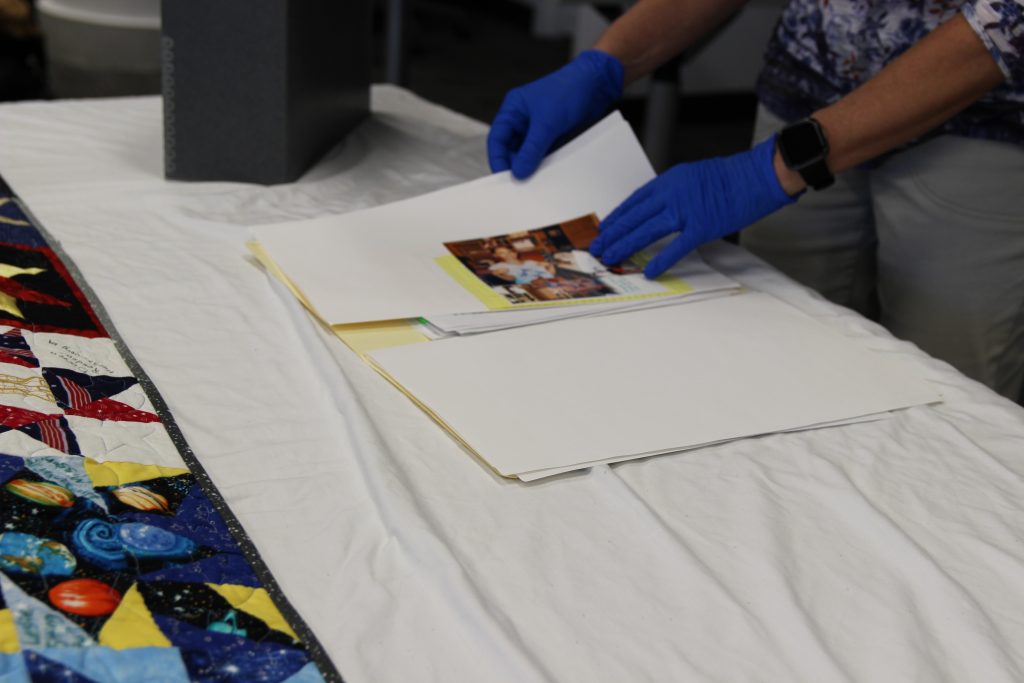

Right: Karen Nyberg examines a group of letters and photographs submitted with the quilt blocks by challenge participants during her visit to the Briscoe Center in 2020. Now part of the Astronomical Quilts! Block Challenge Collection, 2016-316-01.

This episode of American Rhapsody was produced by Ashley Carr.

The audio was mixed and mastered by Ean Herrera and Morgan Honaker.

Guests

Karen NybergEngineer, Astronaut, and Artist

Karen NybergEngineer, Astronaut, and Artist Bob RuggieroVice President of Communications at Quilts, Inc.

Bob RuggieroVice President of Communications at Quilts, Inc. Vicki MangumFormer President of the Quilt Guild of Greater Houston and a Member of Quilts, Inc.

Vicki MangumFormer President of the Quilt Guild of Greater Houston and a Member of Quilts, Inc.

Hosts

Sarah SonnerAssociate Director for Curation at the Briscoe Center for American History

Sarah SonnerAssociate Director for Curation at the Briscoe Center for American History Don CarletonFounding Director of The University of Texas at Austin's Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

Don CarletonFounding Director of The University of Texas at Austin's Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

This is American Rhapsody, a podcast of the Briscoe center for American history at the university of Texas at Austin. American history is many things. But it’s most certainly a Rhapsody quilted together from the ragged patches of many disjointed stories. And yet somehow still managing to form a coherent whole.

Carleton: I’m Don Carlton, executive director of the Briscoe Center, a repository for the raw materials of the past, the evidence of history that we collect, preserve and make available for use. Each episode, we talk to the individuals who helped create that evidence, to the donors who preserved it, and to the researchers who use those collections in their work. And we keep the American Rhapsody going.

It might surprise you that the Briscoe Center’s collections are not only global in their reach – they are, literally, astronomical! One example is a moon rock that was presented to Walter Cronkite by NASA, which is now part of our collections. This episode of American Rhapsody explores outer space through the art of quilts.

While living on the International Space Station in 2013, astronaut and UT alum, Karen Nyberg stitched a nine-inch star-themed quilt block. She and NASA invited crafters and artists to join in and help create a global quilt, inspired by the stars. Nyberg’s single quilt block sparked a worldwide project that resulted in the submission of 2,400 quilt squares to NASA, many accompanied by letters and stories of the inspiration provided by outer space.

A team of NASA and Johnson space center, volunteers quilted the squares together resulting in 28 king-sized quilts. In 2015 international quilt festival founders, Karey Bresenhan and Nancy O’Bryant Puentes longtime supporters of the Briscoe center, gifted this collection to the Center for permanent preservation and research. The Astronomical Quilts Collection joins the Center’s Winedale Quilt Collection, a premier scholarly resource that supports the study of quilts and their history.

In this episode, Briscoe Center, associate director, Dr. Sarah Sonner interviews Karen Nyberg. Their discussion ranges from Nyberg earliest sewing projects as a child to the unique challenges of sewing and space, as well as the connection between mechanical engineering and quilting.

Sarah also discusses the astronomical quilts project with Bob Ruggiero and Vicki Mangum, longtime staff members of Quilts Incorporated. And they’re both key figures in the astronomical quilts project. Along with Karey Bresenhan and Nancy O’Bryant Puentes, Bob and Vicki worked to ensure the astronomical quilts became part of the Briscoe centers, holdings.

These discussions show how historical evidence can be found in many places, even in orbit around the earth.

Sonner: Tell me a bit, just to introduce yourself about your experience and how you became a quilter.

Nyberg: I’m Karen Nyberg, former astronaut. I was an astronaut for 20 years and I’ve also been doing art and quilting and sewing my entire life, actually more sewing than quilting. And so since I retired from the astronaut office last year, I’ve been trying to do a lot more.

Sonner: And one of those quilt blocks you assembled, you assembled during a month’s long mission in space, and it provided the spark for an astronomical quilts block challenge project. And that call for entries resulted in a huge public response. As you know, from people all over the U S and the world, and of all ages and levels of quilting experience too.

They sent in blocks to the project and these were assembled into 28 different quilts. That are now in the collection at the Briscoe Center. And I understand that while they were displayed at Quilt Festival, before they joined our collection, the first chance that you had to spend time with all of them in person was your visit to see the quilts, the Briscoe center. So I wanted to ask, what kinds of discoveries did you make in the process of getting to see all of them and the collection together?

Nyberg: Yeah, I did get to see them the first time at Quilt Festival and it was so different to actually see them up close. When I looked at them at quilt festival, I saw them more from a distance and as quilts, but to be able to look at them close up like that and just to see how unique each block is and what went into the thinking that each person who sent it into all the different countries that they came from, it just was really neat to me, especially being somebody who quilts myself and knowing what goes into the design process and the thinking, like having a, should I have this fabric or this fabric and all that goes into it. And just to know that these people all over the world were putting that into it was pretty neat experience.

Sonner: So you understood the process that was involved behind each one and which techniques were used and those kinds of choices.

Nyber: Yes. And I love to see all the personal touches and that sort of thing that went into each block and the thoughtfulness of each one.

Sonner: And a lot of them were accompanied by these personal notes and letters from people who would send these in, when they were submitting the block. And were there any of those letters in particular that strikes.

Nyberg: A lot of them did. And I actually haven’t had a chance to read all of them yet. When I was at Briscoe center, I took pictures of all of them. So I would have record of them and I’ve gone through and read several. There were so many from people that were dedicating it to family members or friends that used to work for NASA or worked on the Apollo program.

There was one woman in particular who had worked on the shuttle program and she actually used, she had done some sewing for the shuttle program and she used the shiny silver fabric that had been used on shuttle, which I thought was really neat. Some other letters, there was a set of quilters from a guild in Venezuela about nine women or so, and they, they included pictures of themselves holding their block.

And it was just so neat to see that personal nature of it. But yeah, so, so many letters with so many different stories. And there were quilters who had never really thought about space before. And there were space enthusiasts who had never really quilted before. So it was just really neat to see all that come together.

And I can’t wait for the opportunity to finish reading all of those and try to put the picture, the letter with the quilt block.

Sonner: That’s such a great intersection too, from people approaching it from these two different fields and then finding that common ground, especially with that technical fabric that you described. Can you tell me more about that? Was it a fabric shield or like a piece of the spacecraft?

Nyberg: I think that this fabric she used, it’s kind of a Mylar fabric that is used a lot for reflective purposes in space hardware. And I don’t know exactly what the material was, but it’s a really pretty block. It has, it’s kind of a white and then with the silver sewn in with it. So it was beautiful.

Sonner: Yeah, that’s very cool. I know astronauts are only able to take a few personal items when you go on space missions. So what made you think of taking your quilting materials and what was quilting in space actually like?

Nyberg: Most people will take some sort of a hobby with them because we’re living there, you know, you have the weekends and there’s not a lot of free time, but there’s free time.

And so a lot of people bring books to read, or I guess for books online, now more so than a hard copy book and we’ll watch movies. Or there was a keyboard up there that people could play and a guitar, but since my hobby on earth was primarily, sewing and drawing and that sort of thing that I figured I would take some sewing supplies.

So I took just a few fat quarters and I took a little magnetic case with some needles and a spool of thread. And it was all honestly purchased very last minute because we have to get all of our, everything that we, our personal items have to be put on a cargo vehicle that launches ahead of time. And so all of our things needed to be submitted a little bit earlier than our launch.

And then also my last trip to Russia, I left several weeks before my launch because I launched from Kazakhstan. And so I ran into a fabric store kind of last minute and just grabbed three fat quarters and grabbed some thread. You know, it was, I hadn’t at that time, put a lot of thought into what I was going to do with it.

But sewing in space is it’s challenging in a lot of ways. One of the challenging pieces for me is I never really so by hand, and that was my only option. And so. Just that in and of itself, you know, I’m not very good at that part of it, but the hardest part was cutting the fabric because, well, for two reasons, one reason I didn’t bring a good pair of scissors.

And the scissors on space station were really bad and just not, they were great for paper, but they were not good at all for fabric. And then also when you hold the fabric, You can’t lay it down. So there’s no rotary cutting there’s no, no, just driving your scissor along the table. You have to just kind of hang it there.

And so it would be as though you’re standing like you are right now, we’re sitting and hold a piece of fabric up and try to cut it. So that was the hardest. You know, the sewing itself, even though I’m not good at hand sewing, just the holding in sewing, wasn’t a big deal. And another hard part is I only brought about four or five needles.

I did not bring any pins or anything like that. And so keeping the pieces together when they’re floating, but it wasn’t, it was a fun experiment. And I did not accomplish as much as I’d hoped because it was challenging. And I didn’t have as much spare time as I wanted, but it was a fun experiment.

Sonner: Yeah. So things went a little slower in terms of the actual piecing then?

Nyberg: And I had no plan. I had no plan when I left. So in hindsight, what I would do is I would design a block and have it designed before I even leave, but I had no plan. So I just kind of started sewing things together and then ended up with that, with what I ended up with.

Sonner: So it was more of a, an improv than a set pattern per se.

Nyberg: It was.

Sonner: And I know any, sewist at all, will just know the importance of special fabric scissors. That’s just one of the first things that you learn is that cutting things needs to be extremely precise. So, and I also imagine that having a magnetic pin holder was very important. Because I want to just let go of the needle and then it would kind of float.

Nyberg: It would. And it’s actually, I think it’s actually just a little bit safer to drop a needle in space because unless there’s some force behind it when you drop it it’s just going to float in front of you where you drop a needle in the carpet and you’re looking for a long time. And then generally I had thread on the needle when I didn’t have it on the magnet. And so it was pretty easy to find if I dropped it.

Sonner: You mentioned learning to sew when you were growing up and being a lifelong artist and, and sewer, and I wondered if quilting has always been a part of your sewing practice?

Nyberg: Not always when I was really little, because my mom taught me, I was probably six.

She said, I was always asking to use the sewing machine or be taught how to do something with it. And so I sewed a lot of clothes. Through junior high and high school. I sewed little Teddy bears from when I first started sewing little blankets for dolls and things like that. The first quilt I made was I was probably a teenager and it was just square blocks that I stitched together.

And there was no precision whatsoever. I still have that. And it’s yeah, there there’s absolutely no precision to it, but that was my first one. And so it wasn’t until I think graduate school that I did my first actual pieced quilt.

Sonner: And how did that turn out?

Nyberg: It’s good. It’s a pinwheel and it’s kind of citrus colors.

And I had it on a bed in my spare bedroom for a long time. I made some curtains to match.

Sonner: Nice. Are there any patterns, either contemporary or historical that you’re particularly drawn to when it comes to quilt patterns?

Nyberg: Well, you know, honestly since that pinwheel quilt, most of the quilts I make are very, or I’ve made sense are pretty simple pieced together and then applique on top. And I really got more into trying to make it unique with the applique and less about unique with the pieced part of it. So for instance, the quilts that I made, like for my son’s nursery and then for his room, when he turned four and I redecorated it, it was just very simple blocks.

But then I had, you know, Winnie the Pooh applique on the first one dinosaur applique on the second. And so I really started making a lot of gifts for people. Through graduate school. And then once I became an astronaut and it was usually some sort of applique picture on it.

Sonner: So that strikes me that it relates a lot to the projects that you’re doing currently.

I know that now that you’ve retired from NASA, you’re creating artwork based on your photographs of earth from space. So I wondered if you could talk a little bit about how the perspective that you got while in orbit informs how you think about textile artwork, whether that’s through these appliques or some other way?

Nyberg: A lot of it comes in colors. I think because, well, first of all, seeing earth from space is the most amazing thing in the world. And it’s definitely a perspective changer for one. And it just, it makes you feel a lot of things and the colors are so vibrant and I think just like most things, a picture never really does it justice even.

And there are some beautiful pictures of earth from space, but there’s nothing like seeing it with the naked eye. And so even putting that in art is hard because you can’t make it look like you saw it. But I’ve been having a lot of fun trying to find the right colors to show, to make it look more like I looked or make the feelings that I had when I looked at it.

And one piece I did recently, I even exaggerated the pink color of the sand. And that was fun, you know, with some flowered fabrics. So it’s really, I think the colors and then just trying to bring out the feelings that I had when I saw it for real.

Sonner: Like the distance and the detail that you can see there and looking at your artwork, it has a lot of depth to it that I imagine is really complimented by the, like the fine stitching work.

Nyberg: Yeah. I tried to kind of blend the colors together. So that is the piece is it’s really like an applique piece then that I try to blend the colors together. In fact, the style that I’ve been using kind of is I learned, I took a quilting workshop with this amazing artist, Sophie Standing, and she makes animal wildlife pictures out of floral fabrics. And it is they’re stunning. And so I did a workshop with her and that’s how she blends. She does thread painting to kind of blend the colors and to do the details. And it almost looks like she took a pen and drew on it and added the depth that way. And so that, that technique I kind of have taken from what she did just to kind of blend the fabric colors together.

And I also on a couple of my recent ones, I used a little bit of cotton and tried to represent the clouds, the depth of the clouds. So I will use a darker fabric underneath and then the cotton to represent the clouds.

Sonner: So multiple atmospheric layers can show up that way. Yeah. That’s very nice.

Nyberg: That’s my attempt. I’m still honing too. I still, I can’t wait like in 10 years. Exactly, exactly what my technique will look like.

Sonner: I know you have a doctorate in mechanical engineering from UT Austin. And I think anyone who attempts quilting quickly learns that it demands this great deal of precision and planning. And I imagine there was something of an overlap and the technical aspect of these skills is that the case?

Nyberg: It is absolutely the case. There, there are quite a few overlaps. I mean, even from using the sewing machine. And knowing and understanding how to use the sewing machine and knowing what to do when the sewing machine has a problem, but it also teaches the whole design process, knowing what fabrics will work together, what fabrics, what threads, what needles, all of that is very engineering like. And then of course the precision in cutting and the tolerance stackup, that’s possible if you don’t do a good job with that. That’s all very, very relatable to engineering and following design directions. You know, when I used to make clothes in junior high and high school following the directions, you know, and solving the problems that come along with doing that.

Yeah. There’s so much that really, really does relate to engineering.

Sonner: What was your engineering specialty in your career?

Nyberg: Well, I majored in mechanical engineering. In graduate school I honed in a little more on heat transfer and kind of the thermal and heat side of engineering.

Sonner: Hearing you talk about these, the small tolerances and how those can add up over time to maybe skew things or keep them precise really makes a lot of sense, because when you think about stacking up your quilt blocks, you know…

Nyberg: well, when I actually, when I chose engineering, back right out of high school. I chose mechanical engineering because to me that was back in the day before computer aided design. And so we did a lot of the design work on the table, you know, with a pencil.

And that was really appealing to me, that part of it. And that’s what I did. You know, you, you make these, you design your hardware and it’s very similar to designing clothes or quilts or whatever. You know, I ended up kind of veering away from the design side and going into the heat transfer and a little less visual side of it. But that’s why I chose engineering was because of my interest in art or mechanical engineering.

Sonner: It sounds like your career and your hobby have complimented each other really well.

Nyberg: I think so. Yes, absolutely.

Sonner: It strikes me that this macro perspective of earth seen from space is a really interesting juxtaposition to then this fine micro work that’s involved in quilting, an applique where you’re just, are you talking about hand applique with, or machine applique?

Nyberg: Machine, mostly mushy.

Sonner: Yeah. So like you’ve rendered, these whole coastlines are cloud strata, like you mentioned, with these stitches. So I wonder how you see this type of artwork, maybe textile art worker in particular, helping our wider view and understanding of the plan?

Nyberg: I think just drawing attention in general because seeing earth from space really as a perspective changer, and I was so lucky to be able to do it, that I think it’s important that those of us who had the opportunity to fly to space actually share our experiences with others.

And a lot of people have different ways of doing it. You know, a lot of people have written books. And all sorts of different things. And so to me, it’s like if I can share, and I think it’s also important for those of us who have seen it too to share and stress how we feel about the fragility of earth and how we really need to protect earth, because it certainly is a spaceship in space that we’re all crew members and it’s just really important.

And so. If I can do a piece of art or make a piece of art that people are drawn to and then wonder about, and they question it and they, they then maybe look at the picture that I took to make that art and wonder about that and question it and then see where it was taken from. And that sort of thing also though, the connectedness on earth, because I took pictures, you know, obviously over the entire earth.

And so if I can share artworks from different parts of the world, And draw attention to those different parts of the world as well for people that are, that don’t live there, I think would be nice.

Sonner: And the works that I’ve seen of yours to start with. Did you start making coastline views or did you choose the coastlines for any particular reason?

Nyberg: Actually, when I was in space taking pictures, I liked to compose my shots to look artistic. And so a lot of my pictures look like that. And so what I would do is I would see a coastline and in my head, what I saw was a landscape. And so where the water was the sky and then the coast was a mountain or whatever.

And so I have a lot of pictures that I composed in that way. And to me, those are the ones that I think make interesting artworks, you know, almost looks like a landscape. It could be taken as that, but really it’s a coastline taken from space.

Sonner: It lends itself well to abstraction as well. And it has a lot of high contrast possibilities too.

Nyberg: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Sonner: And I, I can see the it’s given you a lot of interesting approaches to fabric choice. Like you’d mentioned bringing out the pink for the sand, so it lets you maybe play with texture or pattern in there.

Nyberg: Absolutely. And I like that. You know, one of them, I actually used a, a flower pattern, a batik, I think, to make part of the clouds, you know, where the, where the flowers are white and the, the rest of fabrics blue and yeah.There’s, I think there’s so much you can do. And unfortunately, I don’t have a limited time to just do this all day because I think I could.

Sonner: When you’re choosing your fabrics, do you start out thinking of, you know, if you’re looking at your photograph and thinking I want to batik for this, or do you explore fabrics and then find one that kind of fits or is it more improvisation?

Nyber: It’s more improvisational. Yeah. I do have one piece that is not of earth, but another piece I’m working on right now, where I decided I’m going to use only batiks for this, and that can be difficult because then you need a certain color, you know, and it’s, it’s hard to find, but most of mine are just whatever fabric I can find that has the color and the texture that I think will fit and work for what I’m trying to do.

Sonner: You mentioned the research that you were able to do earlier at the Briscoe center. And I wanted to ask you, what are your hopes for people, whether they come from a quilt background, or a space fan background, or neither or both, what are your hopes for people who view the collector?

Nyberg: I think I had mentioned this before that one of the neatest things I took away from it was when you look at the quilt from a distance, you see a quilt and it’s not particularly striking.

It’s pretty, it’s a quilt. But when you look at it close up, you see a lot of really beautiful, unique pieces. Each piece has its own story. Each block has, has something about it. That’s unique. And so that, that kind of is the whole world really, you know, and I think this is just a really neat global collaboration.

And to represent that, that especially, you know, I saw the earth from a distance and it’s the earth, but then you hone in on one part of the world and you see a very unique people and places and personalities, and then all those people could come together to make something beautiful.

Sonner: I totally get that. I think seeing quilts from a distance is, and as a non quilter is very different than when you start exploring it yourself and you really understand the intricacies that are involved.

So I can see how that’s kind of metaphorical as you’re talking about the view from space and understanding how these things are fit together and honing in on a particular kind and then zooming out again.

Nyberg: Yup.

Sonner: I know you’re compiling your research and reading through those letters. And I wondered what are you hoping to, to eventually do with that? Are you looking to share that in some way?

Nyberg: I really hope to, because I think it’s such a marvelous story and all of us who kind of got the ball rolling with it were surprised at how big it became. And I would love for more people to see it, to bring it out to the wider community, not just the quilting world, but the wider community and share what we just talked about and how it really represents, um, kind of this global collaboration and worldview of what you see from a distance and what you see, um, close up. So I, I definitely plan to do something with it and I don’t have a definitive plan yet, but, and what I would really love to do, and I don’t know how I would do it, is get in touch with some of these quilters and non quilters and people that submitted blocks and, and talk to them and find out what they were thinking when they did it. And, and, you know, like this quilt Guild in Venezuela, you know, go meet with those women and, um, see where they are now and why they decided to contribute a block. And I think that would be really fun to meet some of these people.

Sonner: There was that quilt Guild. There were other groups of people who submitted blocks as well. I think there were several classroom projects too, where groups of school kids would submit them.

Nyberg: Yes. And some of those sent pictures as well, which was really cool to see. They, you know, they had a project where several kids, you know, got to it. There was one art class, which was a little bit older kids. And then there was classrooms of younger kids and, uh, yeah, those were really fun to see too. And it’s so fun to see the excitement from people about.

Sonner: Yeah, I think the project itself evolved into this great model of what you can achieve with just a visual requests like that. For people to think creatively around this kind of unifying topic,

Nyberg: It really does.

Sonner: So you mentioned earlier that the work that we were talking about was about coastlines in particular, but your latest project is not about coastlines. So what are you currently working on?

Nyberg: I am working on a space shuttle launch. My goal was to get it done before the 10th anniversary of the space shuttle launch or landing. So I don’t know if that’s going to happen, but I was trying to bring out colors in the plumes and that sort of thing. And so that’s in work and I’m, hopefully it’ll be done, let’s say sometime this year.

Sonner: So it’s the shuttle actually taking off? So it’s based on a photo of that?

Nyberg: It’s based on a photo of the STS 1 35 launch was the, which was the very final shuttle launch. Um, my husband was on that launch. And it was taken by, um, Smiley Pool, who is a professional photographer. And I think if I could get it to work though on a too, I think it’ll be pretty neat.

Sonner: So extra personal meaning for that particular launch for you too.

Nyberg: Absolutely.

Sonner: When we were working together, looking at the quilts, I remember you pointed out one and you said, oh, well, that’s that’s paper piecing.

So I wondered how you learned how to get to know different quilt styles or quilt approaches. Was this just like, you know, via osmosis over time as a maker, or did you wa were there specific, um, people who taught you or sources that you had?

Nyberg: It really was more by osmosis. I think when I first decided to make that pinwheel quilt, you know, I went to the quilt store and I, I bought a book, I believe at that point on various designs of pinwheel quilts. And then just start looking online and looking what other quilters are doing. I actually have never tried paper piecing myself. I think it’s just perusing quilts and oohing and awing over quilts and that sort of thing that I just kind of learned, you know, what, what the different styles.

Um, I was going to say there was another one of the paper pieced ones that I really, really loved. Um, oh, “Portrait of the astronaut as a young girl”.

Sonner: Oh, that’s a great title.

Nyberg: Yeah. And it’s, it’s a paper piece, very detailed paper piece of a little blonde girl with a pony tail, looking at a telescope up into the sky. And I just absolutely love that one.

Sonner: I think once you start to handle them relatively frequently, it’s one of those things that you quickly develop, like almost a muscle memory for, because it is a type of object. That’s very domestic. So once you start to see it as, you know, material culture objects, or you start seeing it from the perspective of a maker, maybe, and understanding how those things come together, it brings this whole other dimension at least for me as a person who looks after this kind of collection.

Nyberg: Yeah. I think what this is, while your perspectives about it changes as you learn more to.

Sonner: And I don’t, I don’t think I ever thought a whole lot about technical fabric being used in space exploration until you pointed out that particular square to,

Nyberg: Yeah, there there’s a lot. In fact, I do have a bag of various fabrics that have been used through the shuttle and space station days. Like the orange fabric that is on the launch and entry suits that we wore for space shuttle. That white fabric that is used for the bags that we use for stowage inside station. There’s a lot of external fabric.

You look at the robotic arm, it’s covered with a fabric. There’s fabric all over the place. The different layers of the spacesuit. There’s a Mylar layer, there’s a rubber layer. And then there’s of course the liquid cooling garment, which is kind of a mesh elastic layer that we wear. So there’s, there’s fabric everywhere.

And that would actually be kind of a neat project. Just combine all of those fabric somehow into something.

Sonner: I was going to ask if you were saving that bag of fabric for a particular project.

Nyberg: I actually got the fabric a couple of years ago. I’m thinking I would do something with it. And to be honest, I just remembered it right now. When you said that. Oh, right! I’ve got all this fabric. So. So now the wheels are going to have to start turning again.

Sonner: Excellent. Well, let us know if you do. I would love to see it. I can just imagine this, you know, orange and white and silver and technical mesh creation that could come out of there.

Nyberg: Yeah, I think it could be something, something pretty.

Sonner: I just want to thank you again so much for your time. I just want to feel like keeping chatting, but I know you’re busy, so thank you so much for taking time out of your vacation and your trip to talk with us.

Nyberg: Yeah, it was great to see you.

Sonner: Great to see you and chat again.

*******

Sonner: Bob, and Vicki, thank you so much for speaking with me today about the astronomical quilts block challenge project. But I’ll start by asking if you can describe the parameters of the project itself. What did you ask for in terms of contributions and how did you go about that?

Ruggiero: Sure. So in the spring of 2013, we were approached by a representative from, uh, Kara Nyberg and they wanted us to do some sort of article about the quilter and space, which of course was a very unique thing. In that interview Karen mentioned, she’d be bringing the quilting supplies on the international space. And so we wanted to do something extra and the two of them kind of brainstormed a bit, and maybe they thought about having a video of Karen quilting in space. I know she had done a previous video about washing her hair and space.

It got a lot of social media attention and that kind of went back and forth. And with the two of them finally decided what to do something a little bigger and a little more participatory. So that became the astronomical quilts challenge. And so the idea was that Karen would create a star block while in space on the international space station and create a video with the challenge to voters from all over the world to do their own blocks.

And then what would happen is those blocks would be sent to us and Rana was the coordinator on that. It would be stitched into a large number of quilts, depending on how many blocks we got. And it would kind of coincide with an appearance that Karen would make at the 2014 international quilt festival here in Houston.

Sonner: So did they call for contributions specify just the dimensions and the star pattern, or how much leeway did you give potential contributors?

Ruggiero:We gave a whole lot of leeway. It just had to be some sort of star format and the blocks had to be 9.5 inch square unfinished. So then when it was quilted, it would be a nine inch finished block.

They would all be the same size and the easier to put together into the larger quilts. And we had a one block per person, but we welcome all types of blocks, traditional, modern, and any kind of artsy variation. And we let people be real creative with the color schemes and the techniques that they would use.

Sonner: So what was it like when the responses started coming in? How was it to see the squares and read the letters from the contributors?

Ruggiero: Well, we had no idea what to expect and then the mail came in and they came in more and more. And pretty soon we got to be very intimate on a first name basis with our mail person. In the end over 2,400 blocks from all over the world, come in, including letters from people. I know that we had some blocks that were made by people as young as five and six with their grandparents. Some were done in tribute to relatives, to work for NASA or fans of the space program. And even some were done to commemorate astronauts and programs that NASA had either currently or in the past, including Dr. Nyberg. So the blocks just kept coming in and coming in and coming in and we were overjoyed and overwhelmed by the response.

Mangum: We also received quilt blocks that had to do with the Russian race to space. So we didn’t have a specification that had actually had to do with NASA. It just needed to commemorate space travel.

And so that was why we wanted stars. And then we were contacted by several teachers who had had their elementary age students. Contribute by making something that was space-related to send in mostly on a light background blocks. So there was a lot of drawing and coloring and that sort of thing that doesn’t necessarily interpreted as being a star.

Sonner: A lot of creative license then for this. Were there any particular blocks that surprised you all?

Mangum: Some of them were very professional and some of them like the children’s blocks that was what surprised me the most. And, and when we were putting the blocks together into quilts we decided we had so many of them that we would make it its own quilt. It was all devoted to the children blocks.

I was very impressed by that. And I think the children who participated were very happy to see that they were acknowledged and in a significant way.

Sonner: Yeah. That particular quilt is a really special one.

Mangum: Uh, people for the most part, well, the adults stuck to the theme. You know, the children could only participate on their level, which I find endearing. And, um, had a few people at the so-and who said, oh, I don’t think we should do that. Let’s leave those. And I said, no, we’re not, this is significant. We need to do this because I knew that that would bring parents. And I knew that kids would feel appreciated. And I just thought it was something significant to show everyone that we can all participate at least at some level, and we can all appreciate what each other does and maybe that’s a step in the right direction for other things to happen. But for me, it was just a good way to show that everybody participated and was welcome.

Sonner: That’s a very good point.

Mangum: Yeah. It, because we all know there’s a lot of places we’re not all welcom. So, you know, well worth it to me. And then the one with Karen’s block in it, we tried to make sure that we had NASA related items in that quilt. And Karen’s quilt was always called astronomical quilt one. And the children’s was astronomical quilt two. And they were the same size. We made them larger. And the reason we made them larger was because of the number of blocks we had, that the children made and we wanted to use them all.

Sonner: Was there a way in which you decided how to sort the rest into different quilts or group them?

Mangum: Well, we had a crew of people in the office who made sure they were all the correct size. Now, when you do that, you’re going to lose. You have to fudge. There’s no other way to put it because my nine and a half inch block is somebody else’s not in three quarter inch or 10 inch block.

And they think, oh, they’ll just trim it to fit. Which is exactly what we had to do. And some of the nine and a half inch blocks were nine and a quarter inch blocks. So we grouped them according to what size they seem to be. And so we measured them all again, as we put them together and we tried to sort them based on themes and other than Karen and the children’s blocks, we just tried to keep them pleasant looking because there was nothing except the star theme to hold them together.

We tried to include the USSR blocks in with the NASA blocks, we didn’t want to make a separate quilt that pointed out that these were from some other country and their space race. So we just included them all in with all of them. And we ended up with 28 quilts. No one expected that.

Sonner: I know that you accomplished that assembly and the quilting itself with the help of many hands participating. So how did that process go once you had grouped these together?

Mangum: I have been contacted by several people from NASA who were quilters and they had indicated they wanted to help. So I checked with our company leaders and said, can we have the creativity center for a weekend so we can try and get all these tops put together? And while we were putting the tops together, a couple of the ladies who were helping with that were also machine quilters and said to me, well, you know, you can get these quilted if you just put a call out to machine quilters.

So I did that, but before we started sewing them together, I needed thread. A lot of thread. Everybody needed at least one spool that showed up and did we needed them before we could quilt them. We needed batting, donated. We needed backing fabric donated. We needed finding fabric donated, and I was new to Instagram.

And I just, I knew that a lot of colleagues and related companies were on there that would want to help because they’d want there, we’d give them credit for donating these items, you know, free publicity. So I put a call out on Instagram and boy, I was inundated with people wanting to donate everything, but the kitchen sink.

Sonner: Well, it’s great that social media was helpful in connecting you that way.

Mangum: It was very helpful.

Sonner: I wanted to ask how you see this project relating to the process and the history of group quilting projects? Where there any particular inspirations or models in terms of historical quilts that you all thought of?

Mangum: Well, I just, I knew it could be done. And I’m sure Bob knows from the history of quilting that there, there always been groups have gotten together to sew things together. Once we realized we had so many blocks, we knew that we could then have at least one person working per row are to get them together and then place them so that we thought they looked good. And then, sew all of that together to become a quilt and with the use of a sewing machine that works well. We were just happy as could be. And we spent an entire weekend at the ranch in LaGrange, at the creativity center, sewing all these tops together. And I was flabbergasted. We got them all done.

Sonner: I’m impressed that it only took a weekend.

Mangum: I think there was one or two quilts that Stacy Menard from NASA took back with her and, and her group of ladies. And they finished those up. And once I heard back from people who wanted to do the machine quilting, I sent them off. They didn’t charge us a dime. I sent them backing fabric. They did all of that.

Once that was done, we needed to get the binding and the hanging sleeve on it. So I contact Stacy again and she says, well, why don’t we come out here to the NASA campus? And we can attach all the binding. So we did, and I must have been 30 people who showed up there. I was just flabbergasted at how many people wanted to participate and were willing to spend their weekend to do it several well-known people that included Sue Garman.

Uh, who’s very well known. Uh, I was just amazed. I couldn’t believe it and couldn’t thank them enough, you know, and they all got credit. I kept lists of everything. Everybody who helped Stacy kept the list of the ones that showed up at NASA.

Sonner: I think what we’re talking about speaks to the technical skill and the problem solving that comes into quilting that, uh, non quilters are maybe not so aware of until they participate in a project like this, or they attempt the art form itself.

Mangum: Right? A lot of people don’t understand, what’s involved in the making a quilt, you know, um, should be simple for a computer programmer to figure it out. You got to start somewhere and you want to end over here. So what are the steps necessary to go from A to B? And they don’t realize the cost of it.

Sonner: We were talking earlier about the quarter inch difference in some of these measurements and being able to visualize how that quarter inch difference adds up across a single quilt is a real chance. It’s a real challenge.

Mangum: I mean, uh, for one quarter of an inch off isn’t itch. So if every four blocks you have an inch difference. And when you have 10 of those blocks going across the Creek, You’ve got two and a half inches difference. And if it happens to be more than that, it’s a big difference. Yeah. You think, okay, I can squeeze this one in, but if you’re squeezing and stretching every block, if the quilt top becomes distorted, it becomes difficult to quilt.

It’ll ever hang straight. It, you know, you just, if you were to use it on a bed, it probably wouldn’t matter because nobody’s going to notice that sort of problem, but if you ever intend to hang it on a wall, it’s, it’s quite visible because it starts to wave along the edges and the bottom will kind of ruffle out a little bit.

Or you end up with a trapezoid.

Sonner: Knowing that and having seen all the quilts laid out in person, they are so remarkable and how seamless they look. So. You know, hearing you talk about this, I understand it. But seeing it, I wouldn’t be able to tell that you all have struggled to get them to line up exactly.

Mangum: We did. And we had to decide on some of them, are we going to cut off the point so that this block is the right size? Or are we going to try to stretch it? And we finally decided we didn’t have a choice. We just needed to trim them all to the right size. And if it ended up chopping off a point, then it chopped off a point.

We didn’t have three years to do this. We had one weekend. I was surprised and impressed. We had people sewing these blocks together who had actually never made a quilt top before. They made blocks, but they never made the top. And they were S it was so smooth. And everyone who participated in a particular quilt would hold that up and we’d take pictures of them. It was like, I can’t believe this, you know, it’s, it’s really worked out well.

Sonner: So what is your. If you could speak for Quilts Incorporated, what’s your hope for the collection now that it’s preserved at the Briscoe center?

Ruggiero: We did have one suggestion, although I’m not sure it was entirely serious that we take all the quilts and wrap them around a rocket and then next rockets, all the quilts would go up with it and it would be really cool to look at, but it would be a little damaging to the, uh, to the quilt.

So, uh, I think that the suggestion was turned down.

Mangum: Even Karrie was asking me, well, what are we going to do with these? I said, I don’t know, because we didn’t want to keep them because we knew they were better served somewhere else.

Sonner: They have been processed and available for researchers to schedule visits and take a look through either the quilts themselves or, and or the documentation that came with them and all of the personal letters are really touching to read through.

Mangum: Well, I think it’s really significant. I think this particular call for quilt blocks has been the most successful of any call ever put out for that type of item. I haven’t heard of anything that’s had a larger response. Have you Bob?

Ruggiero: No, I think hands down, anything we’ve done, this has been the greatest response ever. And then going through some of the media coverage. There were stories about this project and Karen and quilting, literally all over the world and from newspapers and magazines and social media, that would never touch a quilting topic normally. So when I think something really great was done with this as really crossed that cross, that boundary and a lot more people could appreciate quilting as the art form that, that it really is.

We’re always looking for ways to introduce the new people who quilting. And I think, uh, the fact that people may blocks that aren’t necessarily quilt and really kind of opened that to people. And one of the, one of the coolest things that I saw was that I would stand by the exhibit when was on display and have people come in and just very excitedly run up to the quilts and try and find their blocks. And once they found it, just the smiles and the joy on people’s faces when they saw that, you know, something they had done in their home was part of some larger, you know, greater project. I think that that really made a lot of people feel, feel good. And it also attracted a lot of people who are not necessarily traditional quilters.

Sonner: Yeah. One of the things that really strikes you about like, when you, and I’m speaking from the first person here, when I go through and look at these. The many different attention and aesthetics that come into it. And like you said, it must’ve introduced so many people to quilting who maybe were just space fans or NASA fans.

And this was their entree into this world.

Ruggiero: Absolutely. And of course the, the icing on the cake was when Karen was able to make an appearance at festival on that proved hugely hugely popular, where she had a big place in the center of the show and was able to do like a slide show with a little bit about her life and her mission in space and, and her level of quilting.

And that was extremely, extremely well attended people, really enjoyed getting to see a real live astronaut who also shared an interest with them.

Sonner: Well, Bob and Vicki, thank you so much for being guests on American Rhapsody.

Mangum:Well, thank you.

Ruggiero: Thank you.

Carleton: This episode of American Rhapsody has been brought to you by the Astronomical Quilts Collection. The collection features 28 quilts as well as correspondence from quilters and articles about the project. It also includes photos and articles about Karen Nyberg photos of the finished quilts and additional documentation.

It’s part of the center’s historical quilt collections, which include the Winedale Quilt Collection of nearly 900 quilts spanning over 200 years of quilt making it also features documentary resources that support research into the role of quilts in American culture, especially during the 20th century. These quilts are a unique kind of historical evidence.

They are powerful visual storytellers that can speak to the history of migration, racism, colonization, slavery, war and imperialism within and beyond the borders of the United States. In addition, the skill, imagination and physical labor evident in the Winedale quilt collection, eliminate historically marginalized women’s work.

People across America have entrusted this evidence to us, and it’s used by people from across America. In addition to inspiring their work. It inspires our own books, documentaries, exhibits, online repositories and digital humanities projects by collecting, preserving, and making available these materials.

We help keep the debates and arguments about who we are rooted in evidence, and we keep the American Rhapsody going. I’m Don Carlton. Thank you for joining us.