First drawn into the fight against racial segregation in the 1960s, Alice Embree became a leader of Students for a Democratic Society at the University of Texas at Austin and embarked on a lifelong journey of social activism involving a wide array of grassroots political, economic, social, and cultural causes.

The Briscoe Center has recently published Alice’s memoir, Voice Lessons, which draws heavily from her papers, part of the center’s civil rights and social justice collections. Alice’s thoughtful memoir opens our eyes to what it was like to serve as an active participant in causes that continue to affect us all.

In this podcast, Alice is joined by Dr. Julia Mickenberg, a professor of American Studies at UT Austin and an award-winning author. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on such topics as US Cultural History; Women Radicals and Reformers; and Society, Culture, and Politics in the 1960s. Dr. Mickenberg also wrote the foreword to Voice Lessons.

Voice Lessons is published by the Briscoe Center for American History and distributed by the University of Texas Press.

To purchase a copy of Voice Lessons, please visit: https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/embree-voice-lessons

Right: Printing at Red River Women’s Press, c. 1978. Photo by Mary Ellen LeBien.

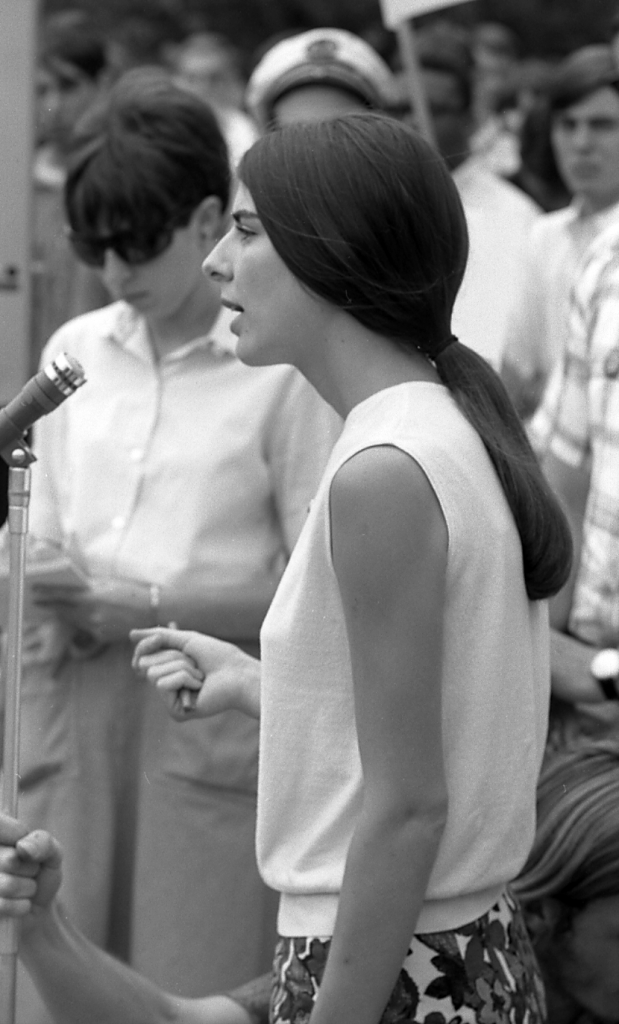

Right: Alice Embree speaking at a University Freedom Movement rally in April 1967, Photo by John Avant.

This episode of American Rhapsody was produced by Ashley Carr.

The audio was mixed and mastered by Morgan Honaker and Ean Herrera.

Guests

Alice EmbreeWriter and Activist

Alice EmbreeWriter and Activist Julia MickenbergAuthor and Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin

Julia MickenbergAuthor and Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Sarah SonnerAssociate Director for Curation at the Briscoe Center for American History

Sarah SonnerAssociate Director for Curation at the Briscoe Center for American History Don CarletonFounding Director of The University of Texas at Austin's Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

Don CarletonFounding Director of The University of Texas at Austin's Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

Carleton: This is American Rhapsody, a podcast of the Briscoe center for American history at the university of Texas at all. American history is many things, but it’s most certainly a Rhapsody quilted together from the ragged patches of many disjointed stories yet somehow still managing to form a coherent whole.

I’m Don Carleton, executive director of the Briscoe center, a repository for the raw materials of the past, the evidence of history that we collect, preserve and make available for use each episode, we talk to the individuals who helped create that evidence, to the donors who preserved, and to the researchers who use those collections in their work.

And we keep the American Rhapsody going. This episode of American Rhapsody focuses on the life of activists and writer, Alice Embree, whose papers are part of the center’s civil rights and social justice collection. These collections chronicle, a range of groups and individual activists working at the intersection of American histories, major social movements.

Together they provide a detailed portrayal of how individuals and organizations employed free speech, the courts, legislation, and other public forums to redress centuries old wrong. The archives revealed a challenging and complex campaigns that American activists have undertaken in pursuit of their causes.

First drawn into the fight against racial segregation in the 1960s, Alice Embry became a leader of Students for a Democratic Society at the University of Texas at Austin snd she joined the anti-Vietnam war movement. At one point, Alice moved to New York to serve as one of the original staffers at the underground newspaper Rat. When Alice eventually returned to Austin, she moved to the forefront of the women’s liberation movement.

She also helped launch Austin’s underground newspaper The Rag. Alice eventually returned to school and earned a master’s degree in community and regional planning. She continues to be deeply involved in a wide array of grassroots, political, economic, social, and cultural causes. The Center has recently published Alice’s memoirs Voice Lessons, which draws heavily from her papers. The books we publish are closely connected to the Center’s collections, like Voice Lessons, many of our publications preserves the historically important memoirs of individuals whose papers and oral histories are at the Center. Alice’s thoughtful memoir opens our eyes to what it was like to serve as an active participant and causes that continue to affect us all.

In this podcast, Alice is joined by Dr. Julia, Mickenberg a professor of American Studies at UT and an award-winning author. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on such topics as “U S Cultural History”, “Women, Radicals, and Reformers” and “Society, Culture and Politics in the 1960s”, Dr. Mickenberg also contributed a preface to Voice Lessons.

Alice and Julia are interviewed by the Briscoe Center’s associate director, Dr. Sarah Sonner, their discussion explores pivotal moments and Embree’s life of protest and change and how present day social activism compares to the movements of the sixties and seventies. Like Embree’s memoir, this episode reveals the power of one woman’s story and how a personal story can illuminate broader historical trends.

******

Sonner: We’ll start by asking you both to introduce yourselves.

Embree: My name is Alice Embree. And I’m the author of a book that the Briscoe is publishing called Voice Lessons.

Mickenberg: My name is Julia Mickenberg and I’m a professor of American studies at the university of Texas at Austin and Alice asked me to write the forward to her book.

Embree: And I thank you, Julia, as you said in the forward five years ago, I think it’s six. Is it six now? And one pandemic in there. That’s when we first met and you’ve been very supportive in the idea of writing this. So I appreciate it. And I’ve learned a lot from going to your classes and going to classes of Dr.Richard Reddick and also Laurie Green in the history department, because it’s the interaction with students that makes me aware that well I’m history and this history of social activism is interesting to students,

Sonner: Alice, your memoir of Voice Lessons is published and in it, you describe in vivid and thoughtful detail about growing up in Austin and your life as an activist and how you grew as an activist, living in the Jim Crow south, and becoming a member of the Students for Democratic Society at UT in the sixties and later joining the women’s liberation movement, they write in detail about certain pivotal moments for you.

One of which was when you were a teenager out with a group of your friends, and one of them was refused service at a restaurant because she was black. What happens on that day?

Embree: I grew up in Austin. My father was a professor in the education department and Austin High when I was a junior was, I would say token integrated.

There were probably 12 to 15 black students. And in the drill squad that marched at football games, Claudine Props was the only black girl in the drill squad. We all went on a bus to a football game and Corpus Christi and we stopped at a restaurant and they don’t let us off the bus. First of all, I’m sort of maybe a clue.

And then we go to another restaurant and we all sit down and Karen Kiki, Claudine and I were all at the same table. I just remember this, some vividly, this waitress who I’m sure was sent out there by the owner coming up to Claudine and saying, “I’m sorry, honey, we just can’t serve you here.” And I stood up and I said to everybody else, they won’t serve Claudine, we have to leave. And then everybody else, just said, “well, we’ve already ordered Alice”. So the three of us left and it was my first personal experience with that kind of what I think of is raw racism of the Jim Crow south. We went to Woolworth’s and we sat down and we ate. I don’t consider what I did very courageous. I’m glad that Claudine didn’t leave and eat alone. And I knew so little about activism then it was all just some, “nothing to see here, nothing to sit here, let it blow over.”

We never got talked to by the chaperones or the anybody, the sponsor of the drill squad, the principal, anybody. It was just kind of like, they put us in this situation and you know, we didn’t know how to escalate it.

So we just kind of lived with it, but it, it just stayed as a very emotional experience for me.

Mickenberg: Do you remember what year was that Alice?

Embree: It was 1962.

Mickenberg: So you knew that you could go to Woolworth’s that, that had been. So you were, you were all aware that Woolworths had been integrated because of the sit-ins

Embree: Because of the 1960s sit-ins in Greensboro and they had begun that. So some of the national chains were integrated, but there were still holdouts in Austin that Piccadilly restaurant. Hold outs on the Drag. And when I was a freshmen in 63, the University of Texas dorms and sports were segregated, I would say civil rights was my entry into activism.

And I got involved with a group on campus working to integrate dorms and sports and other things. And it wasn’t until 70 that a black player was on the UT football. That’s a long time black students had filed suits, et cetera, et cetera. So. what, it happened was that Lyndon Johnson became president and the black students took it to the sidewalk in front of his daughter’s dorm Kinsolving.

Since it got publicity in late 63, when he had just become president due to the assassination, I think that’s really what prompted the university to finally integrate all of its own dorms. Now it didn’t integrate dorms like a Scottish Rite that were privately owned.

Sonner: One of the things that came through to me and reading your memoir and that story of standing up for a Claudine was that it, it felt like a moral imperative. It felt like the right thing to do. And I was curious whether looking back on it, did it seem like a conscious choice?

Embree: You know, it just, I mean, sometimes you just stand up and that’s what I did. And I think to be honest, my reaction to it now, and then was. Why aren’t other people standing up? I think I still live with some sense of awe that other people don’t get up and do some things sometimes when faced with things like that. It’s been a process of getting to understand from a friend, Sandra Kirk, who was a high school student then, what it was like to be among nine black kids at University Junior High. What was that like? Their parents were huge support system in a lot of cases, but bus drivers would pass them by when they tried to get on a city bus to go home and the parents would go down to the best company and go to the Meyer.

That’s what you learned from conversations. Like what was it really like. I just felt like I was able to see that and experience that because I was sitting by the Claudine. I will never get over the way it was said, because it was with such a Southern saccharin sweet kind of sentiment of like, oh, I’m so sorry we have to do this.

You know? And it’s all said in this very sweet way, it just, it made a huge impression. But I, I don’t even remember making a decision so much as just standing up. I mean, we had to stand up or I guess we could have sat there and let Claudine stand up, but that we, we weren’t going to do that. And so the three of us stood up.

I mean, they wouldn’t even let us keep sitting there, I guess. I don’t know what would have happened. My mean, maybe that’s what we should just say. No, we aren’t leaving that, that would have created an incident.

Sonner: It’s remarkable that no one at the school even said anything after the fact that

Embree: Maybe it’s not perfect, but there’s a better infrastructure, I think, for that now.

Mickenberg: You know, it’s part of what’s been so interesting to me in getting to know Alice and her story is I teach a class on the 1960s. I also teach a class that’s a freshmen seminar that’s on college and controversial. And I have teenage daughters who go to public school in Texas. And I learned that in the Texas public schools, this is even before there was a law passed about it.

There isn’t much taught about Jim Crow in Texas. Students really don’t know anything about it. And of course, you can’t study the 1960s without talking about the civil rights movement, but it’s kind of mind blowing for the students to see what has happened at the University of Texas. And it’s super exciting for them to actually meet people who were involved in creating those changes.

When I bring Alice actually to my classes and now with her papers available, being able to work with those papers at the Briscoe, or being able to read her memoir, which is in a sense of kind of narration of the personal story and stories behind what’s documented in those papers. I think it’s really transformative for students and it brings not just a local perspective on these national events.

It makes these, these sort of abstract ideas suddenly seem really real to the students.

Embree: I think that even the word Jim Crow you’re right it was never taught that there was very little taught about the institutional framework that was present in the south. And yeah, there were still poll taxes up until I think the year before I could vote, which was 21 then.

So I could say, well, things are segregated and you could see signs. You could see signs on buses. You could see signs at drinking fountains, where they had the refrigerated drinking water for whites only. All of that was obvious, but the deep institutional framework of it was not obvious. And I think that’s one of the gifts of black lives matter is that it’s become, you just can’t talk about that history without looking a lot deeper now than we looked then. You know, well, we, we got things integrated, but that, of course wasn’t nearly enough.

Sonner: And I think looking at archives like yours and reading your memoir as well, really shows how these kinds of underpinnings have continued to affect things in that daily life and you start to see ways in which the structure is there and it’s invisible to you. Until all of a sudden, one thing happens or you see something or you meet someone or hear someone’s story, and then you see how things keep repeating until we start dismantling that structure underneath it.

Embree: Yeah, I think I always want to say to students that the first thing in the sixties was in fact, the direct action taken by students at sit-ins at lunch counters and students couldn’t vote.

People don’t often remember that the voting age was 21. These were people that took democracy into their own hands and with their bodies begin to change things. I’m sure their parents weren’t that happy with them, at least a lot of them. I think what happens to people is though, well, you know, you learn about democracy.

Well, you vote and you did your job. And, but democracy is, is really about making democracy. And so the combination of the civil rights movement with its direct action and then. Students for a democratic society with its participatory democracy concepts. I mean, they were just revelations. It was like, oh, you can make change.

In fact, you ought to. I remember reading the Port Huron statement and just being like blown away by it. I felt like it really spoke to me. It was written in 62 and I didn’t read it until 64, but it was about taking change. And to participating in the decisions that affect your life. And I’m like, oh, what a concept!

Mickenberg: In thinking about why people would want to read Alice’s memoir? I think for me as a historian, one of the things that is so powerful about this personal story is that through one individual’s life, it lets you directly see the way the civil rights movement inspired SDS and the New Left. And then it lets you see the way in which women’s liberation in many ways grew directly out of SDS and you can see in one young woman’s life. You mentioned turning points, but these eye opening experiences that shifted her attention that made her go all in devoting her energies, sacrificing all kinds of things in order to fight for these various causes. And it’s also exciting. A lot of it is about the sixties and seventies. Alice is still active, you know, and if you look at the collection in her papers that I assume she must just keep adding to them.

She’s always involved in something. When we talk yesterday, she was talking about how she learned so much from young activists now. And that’s part of what makes her so wonderful is that she’s always learning from other people and so humble. But at the same time, I’m struck when she, and some of her partner, you know, comrades in arms or whatever, come to my classes, the students are so blown away by, by how much more active these older people were and continue to be.

It’s almost inevitably the thing at the end of the class that they say that stood out to them was having these older activists come and, um, talk to them about what they did, but just to go back to that point that I was making about the significance, this personal narrative of civil rights, SDS women’s liberation in one woman’s story.

And I can think of other women who have a similar trajectory, but Alice really tells that in a very eloquent way. And there were these, as you said, these turning points where you really see those shifts happen.

Embree: Yeah, Julia always wants me to tell this story. I think that a big turning point for me was the takeover of The Rat newspaper in New York and by women. And I, at that point, I was back in Texas. I had written an essay for Robin Morgan’s Sisterhood is Powerful, but it really was written kind of as a researcher would write it, doing, reading the Advertising Age and listening to what they say to men, women, and watch Soaps and particularly the advertising messages because they spend a lot more money on that than they do on programming. I had a small embrace of women’s liberation, but my partner, Jeff Sherra was in Greenville, Mississippi. And. I visited him and heard her phone call when the women were taking over the paper, like, oh, they’re taking, I could only hear his end of it.

And it was listening. I mean, I will say that since he had started the paper, there might be some feeling of “well, that’s my paper” but it was the dismissal and the expletives of women that really rolled over me and affected me and I and so I came back to Austin with a very different sensibility and began to meet with women.

You know, you talk about Jim Crow and the, the sort of the curtain’s main part in looking at it. And you know, for a lot of us that are grown up was kind of middle-class in the, Eisenhower era, that was the curtains pulled back again. And we were like, oh, we were raised to be submissive, to type, not right. To run the mimeograph machine, to not speak at meetings, even in radical circumstances very much.

And so all of a sudden, all of the ways that there were, we have been shaped were shaken to the core. And I don’t know how much women, I mean, I think women have a different sensibility. They can at least see women in positions of power now, but you really couldn’t very much then. I think that was a huge change for a lot of women and it, in the seventies, it really was embraced by both men and women in radical settings, but it kind of, uh, shook many sixties men to the core when their positions were suddenly questioned. Why are you always talking?

Mickenberg: So, yeah, just to, just to put this in the kind of historical perspective, Robin Morgan’s collection, Sisterhood is Powerful was sort of the groundbreaking collection of women’s liberation writing. I believe it was published in 69, 68?

Embree: Late 69 I think or 70.

Mickenberg: So Robin Morgan and other women also took over this underground newspaper, The Rat. Now one of my favorite books on the 1960s, The Politics of Authenticity by Doug Rossinow, happens to focus on Austin. And I read this before moving to Austin. That was how I knew about Alice Embree.

Rossinow describes Alice Embree and Jeff Sherro as the ultimate movement couple who had met through SDS and were at all the protests together and everything. And I was just, and I continued to be just so struck by that s tory of them kind of in activism together and traveling together. And I don’t know what he was doing in Greenville, Mississippi, but I assume it had something to do with civil rights or reporting on that.

And then I imagine Alice overhearing this phone call and suddenly. I mean, it couldn’t have been suddenly, but maybe suddenly lots of things started to feel different. Like why is he responding this way to these women who took over this paper because they had valid complaints about it? And he’s being so dismissive of them.

And I don’t know that you broke up right then, but that was the beginning of the end of the relationship for the ultimate movement couple. And the idea that it was this very personal thing that shifted your attention toward women’s liberation. I just think is so poignant and it shows like the power of reading memoirs, the way somebody’s own life circumstances will shape their, their activism.

So I just think that moment is really, in fact, I said to Alice, we chatted yesterday and I said, is it okay for me to bring this up? Is this too painful? And she said, well, you know, I agree. It’s an important part of the story.

Embree: Yeah, it’s certainly an important part of my story. It’s a pivotal moment for me. From that point on, I began to meet with women and consciousness, raising groups, form women’s organizations.

I wasn’t a student, but I, a lot of activism was around the campus. I knew the women at Rag newspaper who had kind of silently moved women’s liberation into that newspaper. It was not a takeover, but the women’s content in the paper was very obvious and women’s leadership at the paper. And then one woman, Judy Smith tells a wonderful story.

She’s no longer with us, but she did. Well, we need to do birth control counseling. And so as they literally just took a bunch of plywood and we hammered in a little office for ourselves, I took space in the Rag office, which was in the Y on the drag. And then they began to do birth control counseling. And as they did that, they became aware of, of course of abortion referral needs and was kind of the backstory to Roe v Wade because they were doing the work like that and going well, is this something we can be arrested for? And they begin to sort of look into the legal aspects of it and talk to Sarah Weddington about that lawsuit. In fact, raised money for her, like things like garage sales. It’s always, I mean, it’s like a very low-key grassroots effort.

Leading up to that.

Mickenberg: So yeah, touching major historical issue of our time, tied to the backstory of the Roe v. Wade case. and then for people who don’t know about the Rag, which you were involved in from the beginning, right? Alice, that that was one of the earliest and most important underground newspapers. There were hundreds of underground newspapers in the sixties and the rag was one of the first and the longest running, I believe.

Alice was suspended, partly because of her activism at UT and was very involved in Vietnam war protest, and then solidarity with Chile. I mean, we could talk for hours about all the incredible things Alice does, which also gives you a record of the sort of intersectional concerns of activists in Austin and the sixties and seventies, and one really important one in particular.

Embree: Yeah, my father, of course, was a professor and I was put on disciplinary probation for, I always say for “giving a speech in an unauthorized location”. That was the west mall where we had not gotten a room for meetings because we didn’t have time over the weekend called a meeting and Frank Erwin chose six of us. I was the only woman among the six to be actually suspended. There was a huge uproar, a huge free speech movement that went on and they kind of backed off that and put us on disciplinary probation. So I always say, well, I wasn’t announced by the agitator. I kind of grew up on the campus.

Sonner: UT was a kind of home for you as well, which. Not with your father being a UT professor, especially brought you to Frank Erwin’s attention.

Embree: Yeah. As the Embry girl, that was the word he used for me.

Mickenberg: Yeah. I will say it’s really interesting to read Alice’s memoir in conjunction with Doug Rossinow’s book for the background on it.

So like, one of the things that I think is notable about, you know, the movement in Austin is the involvement of the YMCAs. And the kind of, he just calls it Christian existentialist dimensions of the movement, but Alice was involved in the YMCA. Right? And there were a lot of people in that camp, older people in that community who were supportive of what young people were doing and supportive of integration. And I don’t know if that’s something you want to talk about Alice, but I think it’s an important, somewhat unique dimension. I mean, I don’t know how unique it was. Certainly the black church is super important when you look at civil rights. But as far as the new left, the role of the YMCA and various churches, I think is really a fascinating part of the story.

Embree: Yeah. It was an angle that, uh, Doug Rossinow was interested in kind of the Christian origins and I, what I think is a lot of the support system. The Y had a building at 21st and Guadalupe and then moved to an, to above a drugstore, all, two blocks to the north. So the Rag was housed at the first site, and then at the second, the Methodist student center, which is now a parking lot was just a huge resource for draft counseling and solidarity work with Latin America. We had a vegetarian restaurant there. And then before I got to UT as a student, the Christian faith and life community, that Sandra Caisson, who became Casey Hayden and was married to Tom Hayden and Austin. Anyways, Casey was very active in, in, uh, students for direct action.

And I, they were the ones that pulled off a kind of innovative direct action in the 60s in front of movie theaters that were segregated, that was called stand-ins.

Sonner: That type of resource center that you described with the restaurant and the draft counseling. And then the Y was that something that was characteristic of Austin in particular? Did you see that kind of thing elsewhere during this time?

Embree: Well, I know I did see it elsewhere because I worked for a research grouping in New York called the north American Congress on Latin America. And it had a kind of sponsorship with the national council of churches. Um, the newsletter was mimeograph there.

And so there, yeah, there was definitely a relationship with just as there is now with progressive churches and it’s such an important connection. People don’t always see that, but it is very, an, a very important part of the fabric always has been, I mean, go to El Salvador and you have Bishop Romero was actually assassinated for his liberation theology and he was giving communion in El Salvador in 1980.

And of course you’ve always had people or you certainly saw it in the civil rights movement. We saw it in the new left and you saw it against the war in Vietnam and you see it now you see it with the sanctuary movement for people seeking asylum, who can’t get asylum. And then you have that, and with, with direct resistors, of course, in the, in the sixties, churches would house draft resistors

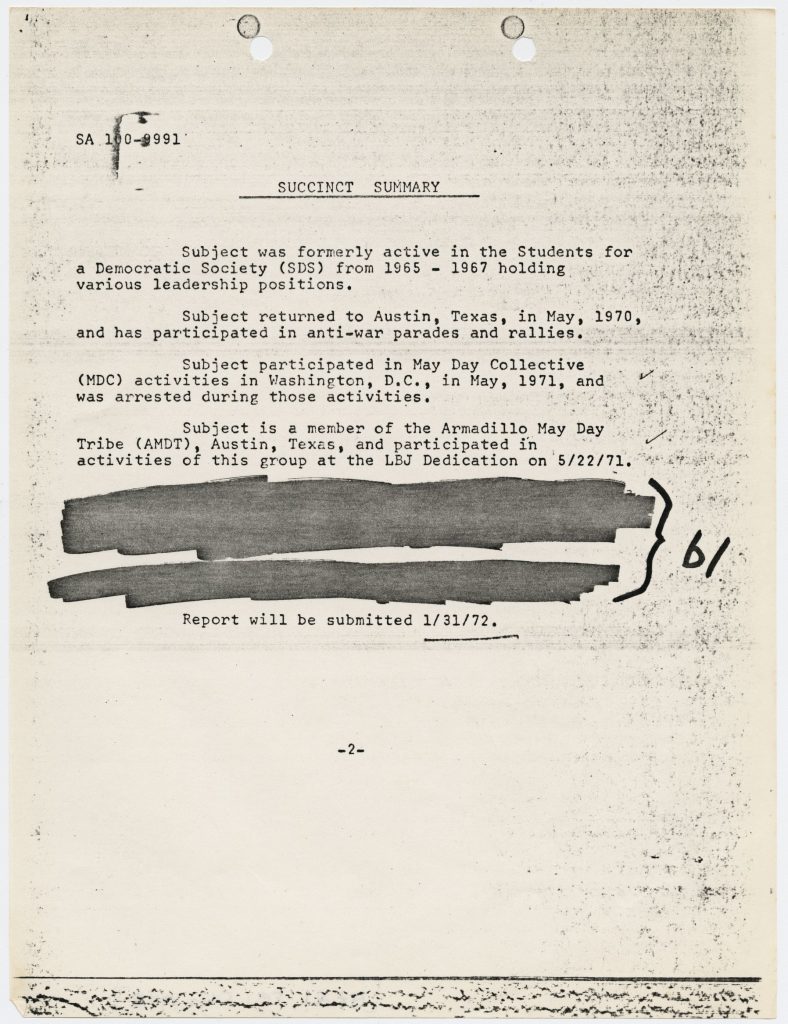

Sonner: Thinking about your time at UT, when you wrote about joining the STS and signing the membership cards and this awareness that it would make you visible to the FBI.

I was really struck by that and how the knowledge of being surveilled was something that you and other activists live with in your work. And. I wanted to ask you about this. And I know you mentioned Bert Girding a few times in the book and we also have his archives of the Briscoe Center. So it’s very interesting to look at these two side by side.

I wonder what it was like for you to, with that knowledge, and then to later read through your own FBI file.

Embree: Well, I requested my FBI file in 78. I did give it to the Briscoe in 2015. And when you read those things, I mean, it’s like almost entirely blacked out, you know, so no sources are obvious. And I mean, to be honest, we, you kind of joke about it, but of course it wasn’t really a joke and they were devoting quite a few local resources, Lieutenant Burt Girding and George Pfeiffer. I mean, and they would come to SDS meetings and I mean, we didn’t try to kick them out if they would sit at the back taking notes and retrospect, it’s kind of like, well, it was sort of a joke, but of course it’s not a joke that you’re concerned a threatened this way. I have never read Burke Girding’s papers, but I’ve seen some, one of the police summaries of the women’s liberation movement. It’s hilarious to Barbara Hines it’s it was her file. And it’s like, well, they don’t see, you know, they don’t shave their legs. They, I mean, it was like the most ridiculous. And of course the real truth of it is that the, that surveillance had deadly affect over and over again, in the black community. And there’s that movie now of Fred Hampton being killed in Chicago and within one year, Carl Hampton, no relation, was killed in Houston. And so over and over, you see the very deadly effect of that surveillance. And there were a lot of COINTELPRO. Kind of, you know, sew division games going on. And I think for a lot, for those of us who knew George Bizard, who was shot, there’s always been a kind of like a question since we ran across a paper where it was mentioned that the person who shot him had volunteered to be a narc.

So, you know, and you just kind of, okay. Deadly effect is a part of it. And I, and we joked that it wasn’t really joke joking manner.

Mickenberg: So one of the things that I’m a scholar of is the Old Left, the Communist Left, people came of age in the 1930s and the McCarthy era of the 1950s. And Alice was saying that one of the things that was so effective about McCarthyism was the way that it created a kind of disjunction in the left because people became so afraid of talking of revealing their politics of making these connections. And the surveillance got much worse COINTELPRO, which Alice mentioned. People might not know what that was the counter-intelligence program of the FBI. It was later declared illegal, but they would put agent provocateurs, they would send fake letters. Maybe Alice would, you know, somebody she’s collaborating with might think she’s getting a letter from them that makes her wonder if they’re actually turning against her. And they really targeted The Black Panthers and the American Indian movement, but they were targeting all of the movements, the new left SDS, everyone.

And so it created this tremendous atmosphere of distrust. So that surveillance was so real. And yet I don’t think it really stopped anybody. Maybe it stopped some people, but it is really interesting to look at that generational difference. The difference between the Old Left and the New Left is sort of large it’s generational, but it’s also the new left sort of trying to cast off the Soviet connection. The Stalinist roots, all that.

Embree: STS started as the Student League for Industrial Democracy. The League for Industrial Democracy was, I guess you could say, oh life, but it was primarily socialist. Anticommunist alt-left. And along the way, STS was like, oh, I’m, you know, and this, this cold war mentality isn’t working for us and kind of abandoned this whole view that everything was, I mean it happening in Vietnam too. So like, oh, you’re going to tell us that the whole reason we are in Vietnam. Because it’s going to be Communist. And then so, but you know, you dig deeper and you go, but didn’t, they just fight a war against the French didn’t they win in 1954 in Vietnam against the French and about, and it was about Colonialism.

You know, it was a matter of national liberation and sort of like being told the half truths always and being expected to just, well, gotta fight communism. It’s a belief that we all could be conned by that one argument when, without looking deeper into what was really happening in Vietnam and with other colonial, I mean, that was a period when after World War II, when colonies rose up and threw off their colonizers and Vietnam was one of those and the US stepped in to help France in 54 and got deeply involved in Vietnam financially prior to getting overtly involved of course, in the sixties.

Mickenberg: But the other thing that you were, I think you’re referring to Alice is the SDS shifting from this focus on class all the time. I don’t mean to put words in your mouth, but that everything can be explained through economics and class.

And shifting from this focus on the proletariat to saying no, students are going to be the lever of change. And that was another, I think, dramatic difference and probably super empowering to young people to think that they could be the agents of change. And they were the ones who recognized that coming back to that example of your friend Claudine and it is amazing. The way kids can see something is obviously wrong and adults will just, it’s like the sunrise movement now. And young people it’s like, everyone knows this terrible thing is going on, but only kids are willing, able or something to recognize it or to say, to open their mouth and say, no, this isn’t okay.

Embree: Yeah. I think one of the gifts. Kimberly Crenshaw, uh, who wrote about intersectionality is a legal argument. There is a greater sense of a lot of forms of oppression combined, and you have to have a certainly class, one of them, but you have to have a very broader view of the ways that people face different kinds of oppression.

I think that something that motivates the younger generation and where I think the New Left kind of got mired into what is the hierarchy of the oppressions? You know, it was like, we have to look at this and this. I feel very grateful that the women’s movement came along when it did, because I think it allowed a much more expansive view for me.

And I still object to, kind of the look of at that, or the characterization of that is the second way. I don’t know what that means, but to me, women’s liberation was a thing of its own that kind of came out of the radical movement and was very radical and felt aligned with liberation struggles. And it seems distinct in a way from.

You’re the historian, the point of whatever the second wave is and the history books, it sort of gets ignored that a lot of the radical women’s liberation people were very multi issue. That’s all.

Mickenberg: Right. Yeah. There’s a, there’s a very limited lumping together of liberal feminism, characteristic of Betty Friedan.

And now with women’s liberation, which was very much coming out of the New Left, SDS, radical politics, civil rights, very consciously working toward intersectionality, even though that term had not yet been invented. And then I think that’s another contribution of the memoir is showing where that feeling of, of no, this isn’t right being indignant is this is coming out of the same place that made you stand up for your African American classmate.

Embree: You asked about the question on voice and I divided the memoir into speaking out and then finding my own voice and writing is of course a voice. It’s a way you express yourself and so 66 from when the Rag was started. I typed and typed and cut and pasted. And I did not think of myself as a writer and it was really not until a year later I was 67.

I was in New York then when Frank Erwin blamed something on the Embry girl that I got this surge of anger, which I think is a very important resource sometimes. And that made me write something for the rag about the chili exchange program. And it was the first time I really wrote. So there’s a way that women ran the mimeograph machines, but didn’t write.

And from that point on, I did begin to write more and more and. You know, there’s of course we have blogs now. So I had the advantage of being able to write that way for the last several years and also for the Texas Observer. But I feel like my voice that creative spark needs to get out. And I really applaud all the writing groups that are out there, all the writing circles, because it allows that and analyze so many more women to write.

Mickenberg: You also asked about Alice’s collection of papers. So if you just read the description of, for example, I’m looking at the pamphlets and Munis miscellaneous literature in her papers, it’s like a list of things people were looking at. There’s the story of the Black Panther Party. The Earth Belongs to the People at College and Power Peoples Press.

The Appalachian People’s History book, Off Our Backs, which is a women’s liberation newspaper. Have you been brainwashed by the Longhorn Christian fellowship? Something from the Gay Blade, the birth control handbook, Cuba for Beginners. John Brown American martyr by Herbert Aptekar, who is like an old leftover historian political program of the south Vietnam national front for liberation.

I mean, I could just go on and on, but you can talk about intersectionality. It’s just like in the list of pamphlets. It’s every cause you can think of it’s an amazing introduction to the sixties is literally just look at the inventory to Alice’s papers.

Embree: Thank you, Julia. And then you can look at the seventies and there’s a lot about Chile and the coup in Chile and 73.

A lot of the solidarity work is detailed there. And yes, I keep saying and I keep, uh, giving things to the Briscoe and they keep taking them and I’m very pleased. There was a woman named Sarah Clark was a staffer at the Briscoe set up social justice collection. And I knew some people that were giving papers there. And now I pretty much an emissary. Well, what are you doing with your papers?

Can you please consider giving them perhaps to the Briscoe and photographs? I think that, that I’ve learned giving things to the Briscoe, that kind of the, the importance of, I mean, certainly a lot of this ephemera is kind of frail and old and so it’s important to put it in a place that can take care of it.

I feel like my life has been blessed by social activism by movements. And I’ve tried to tell young people this too, you make some great friendships. You’ve forged, great friendships and movements and communities. And they last, even when you lose the battle and you still have the community, and we’ve tried to keep those communities alive, but the Rag and now Space City in here.

Sonner: Not really comes through and your memoir as well. I’ll have all of these connections grow and evolve. And I was really struck as well by how we’ve all talked yourself, offset, printing, and control of producing the media too. I thought that was really great. And it includes so many interesting details. You mentioned at one point.

Putting up posters on a dumpster with sweetened condensed milk. And I thought, wow, that’s amazing.

Embree: Yes, and they stayed up for long time. Yes. I mean, my poor professor father, he would have really liked me to graduate on time, but, and I find it funny because Julia says in her forward that I took a leave of absence from the university, but it was really, I think, a 13 year leave of absence.

I was a staffer on campus. When I finished my degree, finally making my father happy that I got one and the first one, I got another one after that, but I was terrible. They go, well, you could get your degree. And I, if I wanted a degree, I can print one, which I always thought it was funny. Cause I could have, I mean, I might not have had the same paper, but I was a printer.

He didn’t think it was that fun, but he was a professor and he spent a lot of his time trying to get people degrees. That was what he did.

Sonner: Well I love what you said about the Briscoe Center and keeping your archives to us. We were really grateful to be able to draw on them for the, On With the Flight exhibit.

And I was curious about whether you went back to any of your archives while you were writing or did writing the memoir make you think about them differently or in a new way?

Embree: Every once in a while, I’d think, I wish I had given that piece of paper there, or at least I wish I had copied it, but I’m, so I’m such a tedious person that I, you know, make copies and make lists.

And so I, I tried very hard to build a chronology from events we never put years on, on leaflets. And that’s, there’s a whole art to figuring out what year a leaflet was that my husband taught me. So, you know, if it says Thursday, July 11, well, then you can figure out what year it was by going to the internet. I did a lot of trying to figure out dates because, and put them all in order does said, I don’t know.

I love Excel.

Sonner: It is one of the most useful exhibit development tools I think that I’ve ever used. And what you described about hunting down the dates is exactly what we do when we go to the label information together, because often it’s just not there and we need to do that backup research to deduce it.

And then you find out what else is being printed around the same time. And Julia, you mentioned that whole list of things that were collected and you start seeing these things in a greater detailed relationship to one another, which is a really fascinating way to look at archives to,

Mickenberg: To mention another repository archive on campus, I love that, like the Harry Ransom Center we’ll collect the whole library of an author so that you can see what books are being read together. And the same thing with seeing all the pamphlets that Alice connected, collected, hardly anybody is like a single issue person. And Alice is such a great. Example of that.

And so to see how a life of activism is actually lived, of course you have to prioritize at certain times. But if somebody is the sort of person who is concerned about injustice, there is all kinds of injustice out there to be found, and it’s all related to each other. And you can see those connections through somebody like Alice.

And I just think it’s so wonderful. Both that she wrote a memoir. And told this story. And I do remember some of our conversations saying, are you writing a memoir or are you, and she was like, well, I’m writing some things down, but, but writing her story down and also saving her stuff and donating her stuff and getting her friends to donate their stuff and just recognizing.

As somebody who spends a lot of time doing archival research. I’m so grateful for that. When I always, I always talked to students about that. Like history is something that we create from archives and from individuals telling us stories, if we do oral history. It’s not sort of just there in textbook form.

And it’s not in those archives unless somebody thinks to save things and donate them.

Embree: Well, I appreciate this conversation and we’ll tell my family that no, I’m not just a hoarder, but have saved things that have been valuable. The interaction with the Briscoe has by me aware of the importance of it. And so I had become something of a conduit for other people.

Sonner: And I always say that one of my favorite parts of my job is digging through boxes with other people’s stuff. And I get to do that. Yeah. Um, becoming a historian was really falling in love with that kind of thing and making these discoveries and getting to know an individual or their personal life and getting that insight into larger historical movements. What you can really get to with an archive.

I wanted to ask what you think about present day social justice movements. You’ve mentioned this growing awareness of intersectionality and that being a real driving force among all of these now. And I wonder if you could talk about how you see their organizing tactics and challenges comparing to SDS and women’s liberation work in the sixties and seventies.

Embree: Well at the risk of sounding terribly Pollyanna a at all. I, and I, I have learned a lot, uh, from interacting with younger activists. If they’ve gone to college, they are straddled with debt in just so many ways. They experience life very differently than 60s students experienced life, even getting an education.

So. The kind of things I’ve learned. I believe they they’ve benefited from the women’s movement in the ways that they facilitate meetings and make sure that, uh, it’s not just the same voices over and over and over and have a kind of step up if you haven’t spoken, step back if you have. They have a kind of progressive stack thing they use and Democratic Socialists of America.

So you, you know, you really. Try to amplify voices that now LGBTQ voices or women’s voices. People of color voices so that you D you know, you, aren’t just hearing the same voices, which I think was a problem in SDS. They are to some degree intergenerational, which is great. I mean, they’ll do allow older people in and they come up with campaigns, organizing campaigns that I think are really well thought out.

I’ve just been very impressed. And I think that with younger activists, That if you just talk about the sixties, the eyes glaze over, I was like, yeah, yeah, yeah. You know, but if you come to those meetings with, uh, with an open mind to learning from how they see the world, and how they perceive change to be possible, it’s pretty exhilarating. And women take a lot more leadership in those situations. I did not experience black lives matter protests. I did not go during the pandemic, but watching that take place as it did. In Marfa Texas or Alpine, or I may just all over the place. I mean, it was truly extraordinary and I think it is a reckoning time and there is clearly all this pushback, but there people are much more deeply aware of the structural nature of oppression now.

And I think that it’s very encouraging to see that for me. And I think there were a couple of decades there where I was like, oh, where are these younger people? But they’re, they’re all there. And, uh, full of ideas. And, um, my experience working with them has been really a learning experience. I’ve enjoyed it.

And every once in a while, then it’s good to hear your story. You know, I have done presentations, democratic socialists of America, about some of the things that are in my book. I think for me, it was important to find a few of the older generation who had remained active in the labor activists. And I hope that this younger generation finds it at least helpful that there’s some continuity with those of us who have remained active.

And I had this idea that continuing ed, you know, continuing it and like if you’re a lawyer or something, Well, continuing ed and activism and continued activism. Because if you go into any organization, now there’s a learning curve and it usually starts with, hi, I’m Alice. She, her, you know, it’s like, there’s a way you have got to kind of get up to speed linguistically, but it’s exciting.

This country’s done a lot of, I think McCarthy was part of it, a lot of work to try to truncate insurgency. So well, nothing to see here, no history there. And then you think, well, I guess we’re inventing it, but you, you aren’t invading it in the more you can learn from the Briscoe or wherever about what went before the more you do it better, and God knows there’s a lot to do. I mean, we have a climate crisis and we have structural racism that we’ve been forced to examine differently and they maybe, this country has examined it before we have. We have economic inequity that I D I don’t think we had, I mean, yeah, it was there, but it was an expanding economy and it didn’t feel like the, we had the 1% or something.

There was sort of a sense of postwar expanding economy that happened, even though there was poverty. So it’s different, it’s global, but it’s exciting.

Sonner: I think that knowing the history and seeing that context that you described helps maintain that tenacity. And you mentioned having that tenacity in your book. And I think that’s something that is a resource that I see how you’ve fed it throughout your work.

And that really comes through with what you just said too.

Embree: I admire tenacity. Yeah. And you do get that if you study history. You know, oh look, we weren’t the first people to think this. Julie, Julie keeps running across all these people that were doing extraordinary things. Women who were doing extraordinary things and whatever, 1930 or whatever,

Mickenberg: And every generation thinks they’re inventing it. And that’s the only other thing that I would add is that when we, I guess traditionally, when we think of activism, we think of young people. All the activism that I’ve been involved with lately, mainly through indivisible, the most active people are all retired. It’s mostly retired women who have the time I’m getting closer to that point myself, but I’m very much still working and don’t have that time.

And it’s really, it’s humbling. And it’s also, it’s just really cool to see that intergenerational people learning from each other. And it seems like nobody ever feels like they’re doing enough. And nobody is ever doing enough because there’s so much to do, but you have every time I see Alice, we run into each other at various protests where we were at the voting rights rally.

I think it was the last one. She’s just a wonderful inspiration and example, and you know, I got interested in her as a historian, but now she’s also just a friend and I’m so proud to be able to call her that.

Embree: Well, I’m, it’s always a joy to see you at demonstration.

Sonner: Well, thank you both so much for speaking with me today. And Alice it’s an honor to have your archives at the Briscoe center and to be publishing processes. Thank you.

Embree: Thank you.

Mickenberg: Thank you. Thank you for publishing it.

Carleton: Today’s episode of American Rhapsody was brought to you by the Alice Embree Paper. The paper span 1962 to 2013. And fully document her civil rights, human rights, anti war, women’s liberation and social justice work. The collection includes correspondence, photographs, ephemera, copies of underground publications and materials related to local civil rights and gentrification.

I want to thank Alice Embree for honoring the Center by trusting her a memorabilia and papers to our care. As part of the Briscoe Centers, social justice holdings, Embree’s papers joined those of Dr. James Farmer, Juanita Craft, Ruth Weingarten, and Abby Hoffman, as well as the field foundation archives and the photography collections of Russell Lee, Steve Shames, RC Hickman, Spider martin, and Charles Moore among many others. These individuals and organizations have entrusted this evidence to us and it’s used by people from across America in addition to inspiring their work and inspires our own books, documentaries, exhibits, online repositories and digital humanities projects.

By collecting, preserving, and making available these materials, we help keep the debates and arguments about who we are rooted in evidence. And we keep the American Rhapsody going. I’m Don Carlton. Thank you for joining us.