This week, we have Prof. John Beckett Wallingford to discuss the current landscape of federal science funding, and the importance of science in American industry and society.

We set the scene with a reading of The Polio Vaccine, Chatham, Virginia, 1964, by Claudia Emerson.

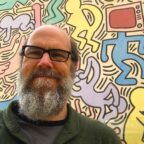

John Beckett Wallingford is a developmental biologist with three decades of experience. He is the Mr. and Mrs. Robert P. Doherty Jr. Regents Chair in Molecular Biology and a Professor in the Dept. of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin. Since 2003, his laboratory has sought to understand how form and function arise in embryos using advanced microscopy, systems biology, and biomechanics. Wallingford’s research explores animal models and collaborates with human geneticists to understand human birth defects. He is writing a forthcoming book about embryos: In the Beginning.

Guests

Prof. John Beckett WallingfordMr. and Mrs. Robert P. Doherty Jr. Regents Chair in Molecular Biology, Professor, Dept. of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin

Prof. John Beckett WallingfordMr. and Mrs. Robert P. Doherty Jr. Regents Chair in Molecular Biology, Professor, Dept. of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Zachary SuriHost, Poet and Co-Producer of This is Democracy

Zachary SuriHost, Poet and Co-Producer of This is Democracy Jeremi SuriProfessor of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Jeremi SuriProfessor of History at the University of Texas at Austin

2025-09-09-tid-federal_science_funding_master

===

This Is Democracy,

a podcast about the people of the United States, a podcast about citizenship,

about engaging with politics and the world around you. A podcast about educating yourself on today’s important issues and how to have a voice in what happens next.

[00:00:20] Zachary Suri: Welcome to our latest episode of This Is Democracy.

I’m Zachary. Today we will be speaking about a policy of the new administration that has received perhaps less attention than many others in the whirlwind of dramatic immigration raids and the whole scale renaming of federal agencies. President Trump’s cuts to scientific research and public health have already had a powerful impact here to discuss the impact of these cuts is a leader in the field of molecular biology.

John d Wallingford is the Mr. And Mrs. Robert p Dougherty Junior Regents Chair in molecular biology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on genetics evolution and developmental biology. Professor Wallingford, thank you so much for joining us. Thanks. Great to be here. Great to have you.

Um, before we begin our discussion with Professor Wallingford, um, we will, uh, as always begin with a poem. A poem about one of the greatest scientific miracles, uh, of the last a hundred years, perhaps polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk in 1955, and whose distribution was paid for by the federal government.

This is. The polio vaccine, Chatham, Virginia in 1964 by Claudia Emerson. It was not death we came to fear, but her life, her other birth, what? Waking remade from the womb of that disease. One leg was withered, a dragging numb weight behind her one shoulder humped camels. And what did we know of that foreign beast, but ugliness and that she carried in it hard faith like water.

And so we did what we were told outside the elementary school, the long line drows. We saw gleaming trays of sugar cubes rose pink with the livid virus, tamed its own undoing. We opened our mouths, held it on our tongues, and as with any candy, savor, the sharp corners going the edges until at last the form gave way to grain to sweet sand.

Washing against the salt of us. Um, well, I wanted to start with our discussion with this poem, um, because I think it captures the human quality of a lot of the complicated science and scientific funding mechanisms that we’ll be discussing. Uh, today. I wanted to ask Professor Wallingford, first of all, how do you think of the human impact of your research?

Um, and who do you have in mind when you, you know, are in the lab and working on, on, on, on molecular biology?

[00:02:46] John Beckett Wallingford: Right. Well, I mean, I, I, I should stay first and I, I, I’m a basic scientist. One of the great pleasures of being a basic scientist is that I don’t have to worry immediately, uh, who my research is for.

Our, our, our job is to really just discover how life works and a lot of the key things that, uh, we consider biomedicine today. Uh, come out of fundamental discoveries. CRISPR came out of research into single cell organisms and, uh, who knows? A, a, a, any number of discoveries, uh, out there. I could go on all day, but, so at the end of the day, I’m trying to understand how embryos develop.

And even though I work in frog embryos, the reason this is really important is that pretty much all embryos, you and me, and frogs and flies and worms, we all use the same genes. And so the work that we’re doing to understand how frog embryos develop is sort of directly related to, uh, problems that go wrong with human develop.

And that’s important because defects in human development are the single most lethal disease in children. This doesn’t get a, a, a lot of, uh, traction, uh, in the public’s mind, but birth defects kill actually twice as many children as cancer. Um, so I think it’s a really important problem.

[00:03:58] Zachary Suri: Professor Jeremy Siri joins us as well.

As always, he’ll ask the next question.

[00:04:01] Jeremi Suri: Sure. So John, that was a really wonderful description of your work and how important it is. How do you judge other scientists on their research? And I ask this question because I think one of the challenges we have in a society. Is judging people on their science and not on their politics.

Right. So how do you judge the quality of scientific work in your field and in other fields?

[00:04:24] John Beckett Wallingford: Wow. I mean, that’s a great and complex question. I think the first thing I would say is that. I’m competent to judge other scientists work because I went to school for many, many years and practiced for decades.

So I think it’s important to know if you’re, you know, your average scientist like me, uh, we’ll go get a PhD. That’s about six years. A really good comparison is the four years it takes to get your medical degree. It takes about five and a half to six to get a PhD in molecular biology. Just like doctors who can’t get a job straight out of medical school, right?

They have to go do a three or four year residency program. Same with scientists. I did four and a half years of postdoctoral research after my PhD, and it’s only after that postdoctoral research, after you’ve been training for about 10 years, that they consider you really eligible for a position as a, as a scientist, as a research scientist running a laboratory.

So the, the way I judge it, uh, is, is, is really, really complicated, right? It, it’s a matter of looking at the data they produce. It’s a matter of watching over time to see if other people can reproduce that result. Um, and, and, and myriad things go into it, Jeremy, and it’s a, it’s a long-term thing and it is one of the reasons that it’s so tricky.

It’s very hard to bullet point, uh, oh, this, this person’s good and this person’s not so good. Um, yeah, it’s complicated.

[00:05:47] Zachary Suri: Professor Wallingford, um, how have you and your colleagues at UT experienced these cuts to science funding so far? Have you been impacted at all by the reduction of these funds?

[00:06:00] John Beckett Wallingford: I luckily have not.

Um, I know my colleague, Jason McClellan had a big grant for some of his vaccine work that was sort of pulled, uh, immediately without any warning. Um, and it’s been an interesting six months or so, but I’m happy to say I’ve come through relatively unscathed.

[00:06:20] Zachary Suri: That makes sense. From your perspective, why are these funds, the, the, the funds that are being cut or at least threatened in our moment?

Why are they important for the work that you do? What role do they play in the broader research field, these federal funds?

[00:06:35] John Beckett Wallingford: Yeah, so I think this is a really, really important thing to understand. So, uh, just to give a little background, I run, um, what, what would be considered a medium sized lab. I have between 10 and 15 people in my lab and I like to tell people that my laboratory is like a small business.

Uh, the thing that we produce is called knowledge. Hmm, right. We don’t sell it, but it takes money to produce knowledge and to produce that knowledge. We get money from the NIH, my laboratory, like I said, as of right now, about 14 people. That’s a couple of really long-term, very well-trained PhD level staff scientists.

A handful of trainees, both graduate students and postdocs who are paid full-time. I think this is a really important thing to understand that graduate students doesn’t mean you’re sitting in class for five years. It really means you actually go and you work in a lab for five years learning and making mistakes and correcting them and getting better over time.

Uh, I also have a lab manager. I have several undergrads that work on an hourly basis. It’s, it’s sort of a really interesting economy there. And all of those salaries from the senior people who are putting their kids through Austin schools to the youngest people whose hourly wages putting gas in their car, uh, those people are all paid for by NIH dollars.

And so I think a really important thing to to know is that when someone says, I got a grant, if I, John Wallingford, get a grant. It doesn’t go to me, it goes into the UT coffers and I use it to pay the salary of UT employees. So that’s, that’s the most important sort of direct thing. But I wanna say one other thing, and that is that, you know, like any other small business, we use goods and services, we’re integrated directly into the entire economy, uh, of Texas.

Delivery people, uh, technicians who come in, we’re buying goods and services all the time. Uh, and so there’s a really important sort of, uh, economic argument for NIH funded labs. There’s hundreds of them at ut and this is putting aside the science that we do. Uh, this is a straight eco economic argument for, for the importance of the NIH.

[00:08:40] Jeremi Suri: And, and John, if I might, I wanted to follow up on that. Um, it, it’s clear you’re running a business and, and, and it’s, I’m always amazed how scientists are able to do that, to do cutting edge science and to manage, uh, the kind of complex team that you do. Why is science so expensive? I think one of the things people don’t understand, um, is when you’re doing re research on birth defects, uh, how expensive it is to actually do that research and why grants are absolutely essential.

Why there really aren’t any other sources of the funding. Can you, can you elaborate on that for us?

[00:09:14] John Beckett Wallingford: Yeah, absolutely. That’s a great question. I mean, why is science expensive? Uh, I, I, I, I actually will sort of address this with, with a bit of a joke, uh, when my students in my class say, oh, the test was so hard.

Or the PhD students in my lab might say something about, oh, whatever is so hard. And I try to explain. I say, well, we’re molecular biology. Students or molecular biology professors, we’re doing what’s considered to be a hard thing at a top university. Uh, it’s meant to be hard, right? It’s really, really complicated.

And so where do the expenses come in? The expenses come in partly to pay the salary. Uh, we’re very fortunate the United States, the federal science infrastructure allows us to hire all these people to do this research, and that’s where a major cost goes. But the other thing is that the instruments are cutting edge.

A lot of what we use microscopes, uh, are very expensive, and that’s because my microscope is not like the one you remember from high school. My microscope takes up an entire room. It has five lasers on it. Uh, it has, you know, a camera alone is $35,000. I remember when I started my laboratory, I bought my first confocal microscope.

And I closed on my house the same week and I’ll let you pick which one was more expensive. And so, so the equipment is expensive, and that’s because we’ve actually moved out. You know, the cutting edge of science is, is, is is way out there now, right? Simple experiments that you might’ve been able to do 80 years ago, you simply can’t do anymore.

And so the chemicals, we need the biological reagents. We need the instruments, we need it, it all adds up. And, and this is what’s necessary. And,

[00:10:56] Jeremi Suri: and just to follow on, John, why, why can’t you rely on industry? Some might say, well, you know, there was a time when Bell Labs, you know, did its own research. Uh, why do you need the federal government.

[00:11:09] John Beckett Wallingford: I think industry has to make a profit and we don’t, and there is a hundred year history of showing that industry does a lot of things really well. Right. Uh, and there’s a hundred year history showing that academia does a lot of things really, really well. Uh, I study embryonic development and there have been about seven Nobel prizes for the embryo in the past 30 years.

Three of those were using worms, one was using flies, one was using sea urchins. One had frogs, only one actually involved human cells. Uh, and they were pretty much all run by people who were just exploring the mysteries of life as we know it. And then they find something, they find a toe holt, they find a way that you can get in and instead of just understand biology to manipulate it.

And then it’s time to hand it over to industry and they’ll do something with it that’s gonna directly impact people’s lives and directly maybe make that company some money. But the only reason industry works is ’cause there’s this massive foundation of people like me out there just figuring out how life works and how we might use it to our advantage.

[00:12:20] Zachary Suri: And without the sort of baseline federal funding that’s now, uh, up, up, up for discussion or, or at least under threat. What kind of long-term impact do you think this will have on that kind of exploratory research

[00:12:35] John Beckett Wallingford: can’t be done without it. Um, simply nobody funds this. I mean, one of the things that I think is so great about America and that has brought scientists here, the people have worked in my lab from 11 different countries.

Um, this federal funding for basic science is uniquely American. No other country does this at this level, and no other country comes close to being able to compete with us in, in, in our sort of, uh, uh, you know, with our scientific power. Um, and so I think without NIH funding, that would be completely impossible.

It is worth noting, uh, and I’m really actually excited to see this. The president had called for a 40% reduction in the NIH, but the Senate Appropriations Committee, uh, disagreed and they came up with actually a. Almost a half a billion increase in the house, actually just last week. Agreed to some number.

Fairly similar to that. And so I’m actually really excited to say that I think a lot of people have been really active to point out the importance of the science. Not only do we need the science to be competitive in the world, but it’s an economic driver and it seems like, at least in the House and the Senate, they’re listening.

So I’m happy to see, uh, what’s gone, gone on recently, uh, with those deliberations.

[00:13:46] Jeremi Suri: And John, that’s good news. Very, very good news. Very good news.

[00:13:49] John Beckett Wallingford: Yeah.

[00:13:50] Jeremi Suri: I I wanted to follow up also on the talent issue. I mean, one of the things you said that’s so interesting is how many years you and others in the field put in be before you really even get your foot in the door, right?

When you’re a postdoc and things of that sort and, uh, how much talent that requires, how much drive that requires. Uh, I’m, I’m sure in your field there are a lot of researchers who are not American citizens. Um. How have recent changes affected, uh, talent recruitment and what do you see going forward?

[00:14:22] John Beckett Wallingford: Yeah, so it’s definitely made it harder, there’s no question.

Um, I’m lucky enough that, uh, I haven’t personally seen any of this, but probably most people know about Ksenia. The Russian researcher at Harvard, she actually works on the same frogs I work on. I’ve met her at meetings before. Uh, and, and the kind of treatment where you have researchers doing something like that.

Uh, so if you’re not familiar with the story, she brought some frog embryos illegally in her luggage on the airplane. This would’ve been, you know, two years ago, a $500 fine. And she was shipped off to basically a prison in Louisiana for a couple of months. And they’re bringing now felony charges of smuggling against her.

And, and all of this, it has a very chilling effect on the people who are gonna want to come and do science in the United States. Uh, and I think that’s really unfortunate. I think that for a long time we’ve been able to count on the scientific infrastructure here, drawing talent from all over the world.

And, and, and Jeremy, you said it exactly right. This is a hard job. It’s really hard. Uh, lots of people want to do it. Uh, you can’t be guaranteed to do it, and you’re not really gonna find out whether you succeed for 10 years. And so it takes a really special kind of person to even give it a try. And I think that we want that pool of people to be as big as we can possibly have it.

And so I do think some of the immigration decisions that the administration has made recently are, are, are, are not helpful in that regard.

[00:15:54] Zachary Suri: We wanted to ask as well, um. How do you think scientists who are doing this kind of NIH funded work as you are, um, can explain why their work is important or why it matters to ordinary Americans who maybe aren’t, don’t have the expertise you have?

[00:16:09] John Beckett Wallingford: Yeah, that, that’s a a great question. Um, and, and I think it comes down to what something we were talking about before and, and that is sort of the complexity of it all. Uh, it takes, for example, let’s say I’ve made some discovery and I wanna translate this into. Um, some kind of drug. That process takes years and most of them don’t work right?

And so the number of drugs that go into the pipeline to be tested for whether they’re safe and then tested, where for whether they’re effective, usually end up not working that well. And so as a result of that, uh, it, we have to do it a lot. You can’t just say, Hey, oh, I’ve got this new drug. It’ll work and we’ll just wait five years and we can start trading patients.

Instead, you have to sort of think of it like a huge funnel, right? You need to have this massive funnel, and that funnel is 10 years long, and so if you want to come out of the end of that funnel with one usable drug that really treats a patient. Then think about how big the opening of that funnel has to be.

And I’m out there at the opening of that funnel. So it might take five or 10 years to bring a drug to market once you’ve got the discovery. But every discovery takes five or 10 years too. And this is why the PhD takes so long. You can only get the PhD when you discover something new. And it takes about six years for someone to come in here, learn how to do it, and actually discover something new.

And so it’s just that complexity that’s that’s why it’s expensive. Uh, that’s why it takes so long to train. Uh, and that’s why it’s hard to grasp for regular folks who, who don’t have a, who haven’t, you know, lived in the sciences, why you need this. What we do seems completely mysterious for the first several years until finally I can say, oh, then I gave this thing to pharma, and then several years later, oh, here’s a drug you can give to your kid.

And so I think that’s why it’s, it’s, it’s important and it, and it’s hard to put into really specific terms, uh, what it is that we do every day, but that’s why it’s important.

[00:18:07] Jeremi Suri: YY you know, John, I, I love that description because it does overlap with what we do as, uh, historians, as humanists and social sciences.

Too, you know, people have this image that, you know, we go into the archive or we look at the data set and the answer is immediately obvious. Uh, what they don’t realize, and I think it’s what you’re describing, is that the work of discovery involves failure after failure after failure. And it’s, it’s, it’s the roads that don’t lead to Rome that eventually lets you figure out which is the road that leads to Rome.

[00:18:38] John Beckett Wallingford: Right. No, that’s exactly right. But you still have to pay the toll on every one of those roads.

[00:18:43] Jeremi Suri: Yes, exactly. Exactly.

[00:18:45] Zachary Suri: Right. I, I want to ask too, um, do, do these sort of federal programs and federal agencies also kind of provide a space for scientists like yourself to work with and collaborate across, you know, different institutions, right.

Someone at the University of Texas maybe work, working on a project. And you mentioned also a researcher, I think at Harvard who was working on similar, uh, in a similar experiment. So does, do these federal agencies and, and, and federal grants also provide a kind of network for you? Uh, absolutely they do.

And, and

[00:19:16] John Beckett Wallingford: they do it in really direct ways. So, uh, most of my grants, I’ll actually solicit letters of support for collaborators. And some of my key collaborators that I’ve been working with for many, many years, uh, are at Washington University in St. Louis. They’re pulmonologists, they’re doctors who work with patients, uh, with developmental diseases.

Uh, have other collaborator at UCSF that I’ve been working with for 20 years. Um, and this all goes, uh, right into those grants. And so when in several of these grants, we write them together, sometimes those guys are, are what are called co-investigators, which means they’re formally attached to the grant, and they might get some part of the money that comes with the grant.

But in the many, many other cases, they’re simply letters of support saying. Yes, I’ve been working with you on this project, and yes, I will continue working with you on this project because one of the things the NIH wants to do is to make sure that you’re doing the work right. That you know where it’s going, right?

So even though it’s this basic discovery, we’re just trying to find things out. It is our job when we apply to the NIH to explain why we think this would be useful, how do we think we’re gonna get to that drug 10 years from now? We have to write that into these grants. And so I think it’s really important also that your listeners understand that when I write these grants, my chance of actually getting one is about 9% right now, which means.

For every a hundred grants I write, 91 of them get rejected. Uh, this is a very selective process. It’s very hard to get these grants, um, and you really have to cover all the bases and a lot of time what that means is finding the right collaborators and fitting it into the exactly the kind of network you’re talking

[00:20:56] Zachary Suri: about.

Great. And you also mentioned that you often have a lot of students working in your labs, both grad students and undergrads. What kind of training or, you know, learning goes on in the lab space beyond the discovery that you’re working on?

[00:21:10] John Beckett Wallingford: Right. So, I mean, I think the, the most important part though of that is just what, uh, Jeremy was talking about.

Coming in, doing the experiment, seeing it fail. Uh, you know, it is not uncommon for a student to work every day, 40 hours a week, full-time job. Uh, for two years and have nothing to show for it. I, I actually say that in a lot. In most fields, if you go to work and you work for two years, you’ll have something to show for it.

But if you had a big hypothesis and you designed a really good experiment that was complicated, and then you went and performed the experiment all the way through to the end, but your hypothesis was wrong, then you’re just done. Right? That’s two years down the drain, which is why you don’t have just one hypothesis.

You don’t just test one thing at a time. But, uh, it, it, it’s really a complicated process. And so what the NIH funding does is to support these students. As I said, the grad students, they’re called students, but really what they are is research assistants. They’re working in the lab all day, every day.

They’re pipetting fluid into test tubes and putting things on microscopes. Uh, and that’s what they’re doing. And we’re paying them a salary while they do it because it’s essential that they do the work. It, it, it really is this. Combination of work and training that you can’t, you can’t separate the two.

They’re one and the same thing.

[00:22:24] Zachary Suri: That makes sense. What, what would you say to our listeners, maybe who, who aren’t undergraduate students or graduate students in your field? But are interested in, in what they can do to support the kind of research that you are doing or just interested in learning more about it?

Where would you direct them? I think,

[00:22:40] John Beckett Wallingford: uh, as a guy who’s writing a book about embryos, the best way to learn about what I do is to wait about two years for my book to come out. Uh, but I, but I do put, I do send people to popular science writing. I really think there’s a lot of fantastic writers out there.

Uh, the New York Times Science Times is really great. The Atlantic does quite a bit of good science writing, uh, but as an old school guy, I would say go to the bookstore and ask to be pointed to the science direction and go browse it and just read. That’s the best way I think to get, to get informed about things.

If you want to add advocate for things, there are groups like the American Association for the Advancement of Science and other sort of science advocacy groups that you can get involved with and, and you can just do a Google search search and find those.

[00:23:27] Jeremi Suri: And, and, uh, John, what about, um, getting young people in particular, but also older people to understand the value of science in general?

I mean, I think one of the challenges we face today is, uh, in part because of technology. Um, people aren’t reading books and they’re not going into laboratories. They’re not going into libraries. Um. What is it we can say to young people and others, uh, that will get them more interested and will convey to them why this is so important.

You know, Jeremy, I, I, I think about this a

[00:23:59] John Beckett Wallingford: lot and I’m gonna turn that question on its head. I, I think that we can’t go out to people in the regular public and say, Hey, you should go find a scientist at a lab. I think scientists need to be better at explaining what they do. So I took up the challenge to write this book basically because I didn’t believe that there was a great.

Readable book about embryos, uh, that I, you know, I just thought, okay, well surely this needs to be done and, and, and I’m gonna give it a try. And I have no idea this, I’ve never written a book before. Who knows how it’ll go, but I’ve really been asking my colleagues to try to get out there. And put stuff into regular words for people so that the people who are doing the cutting edge stuff, uh, the stuff that I couldn’t explain to you until you had been in the field for 10 years and, and be able to translate that directly to people who’ve never taken a biology course and explain why it’s important, um, and, and making those connections.

I think scientists need to be doing a better job of that. It’s something we historically have sort of stayed away from, and I think that’s been to our detriment.

[00:25:04] Zachary Suri: That makes a lot of sense. Um, well, thank you so much for joining us, professor Wallingford. I think you’ve really given us a, a powerful, uh, testament to the power and importance of, of science in our world today.

How it, how it remains relevant, uh, and, uh, maybe, uh, a lesson too for, for scientists and those doing the kind of work that you do about the importance, uh, of communication. Um, thank you for joining us, uh, today. And, and thank you also to to Jeremy for, for joining us as always. Wonderful. It’s a

[00:25:33] John Beckett Wallingford: pleasure.

Thank you for having me.

[00:25:35] Zachary Suri: Thank you. And thank you to our listeners for joining us for this, uh, latest episode of This Is Democracy. This podcast is produced by the Liberal Arts ITS Development Studio

and the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Austin.

The music in this episode was written and recorded by Scott Holmes.

Stay tuned for a new episode every week You can find this is Democracy on Apple Podcast, Spotify and YouTube. See you next time.