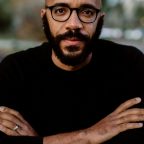

Clint Smith is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He is the author of the narrative nonfiction book, How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America, which was a #1 New York Times Bestseller and was longlisted for the National Book Award. He is also the author of the poetry collection Counting Descent, which won the 2017 Literary Award for Best Poetry Book from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association and was a finalist for an NAACP Image Award.

Clint received his B.A. in English from Davidson College and his Ph.D. in Education from Harvard University.

This episode of Race and Democracy was mixed and mastered by Will Shute.

Guests

Clint SmithStaff Writer at The Atlantic and Author

Clint SmithStaff Writer at The Atlantic and Author

Hosts

Peniel JosephFounding Director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin

Peniel JosephFounding Director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin

Welcome to race and democracy, a podcast on the intersection between race democracy, public policy, social justice, and citizenship.

All right. Today, I am joined in conversation with Clint Smith, who is an award-winning author and poet, and the author of how the word is past a reckoning with the history of slavery across America, which debuted at number one on the New York times bestsellers list. This spring, Clint Smith. Welcome to race and

democracy.

It’s good to be here with you.

This is one of my favorite books of the year. Uh, we’ve had a chance to talk about this, not on this podcast first thing’s first. What inspired you to write this book? I know you are a poet, a writer, you’ve Harvard PhD. Um, and I think you get the blend of all of that in the writing, the writing.

And so. It’s so gripping and so novelistic in a way, even though it’s non-fiction and I know you’re from new Orleans, uh, by the end of the book, you’re, you’re interviewing your grandfather and your, your, your grandmother. So there’s a family, familial intergenerational story here as well. But what inspired this book?

Yeah. Well, I really appreciate you saying that that’s, uh, it’s very generous of you. Um, I mean, what inspired the book in, in 2017, I was watching several Confederate statues come down in my hometown in new Orleans. So statues of Robert E. Lee, PGT Beauregard, Jefferson Davis, these leaders of the Confederacy.

And I was watching these statues come down. And I was thinking about what did it mean that I grew up in a majority black city in which there were more homages to enslavers than there were to in-state people. And what are the implications of that? What does it mean that to get to school? I had to go down Robert Lee Boulevard to get to the grocery store.

I had to go down Jefferson Davis Parkway that my middle school was named after a leader of the Confederacy that my parents still live on the streets. Named after someone who owned over 150 and slave people, because, you know, we recognize that symbols and names and iconography, aren’t just symbols. They are reflective of the stories that people tell.

And those stories shaped the narratives that communities carry and those narratives shape public policy and public policy shapes the material conditions of people’s lives. And so that’s not to say that taking down a 60 foot tall statue of Robert E. Lee or making Juneteenth a federal holiday is suddenly going to erase the racial wealth gap.

But it is to say that it helps us recognize that all of these things are part of an ecosystem of ideas and stories to help us understand more broadly, uh, the history of this country. And also specifically what harm has been done to different groups of people throughout the history of this country and better positions us to make a meant for that harm.

And so I was really looking around and thinking. Well, how my own city reckoned with, or fail to reckon with its own relationship to this history, a city that the historian Walter Johnson, you know, he says of new Orleans. The whole city is a Memorial to slavery. It’s in the roads and slave people paved it’s in the levies and slave people built it’s in the buildings and the homes and slave people constructed.

Often, unmarked burial grounds where enslaved people are laid to rest. And I wanted to get a sense of, well, who’s telling this story honestly, and thoughtfully and robustly and, and what are the ways that this story continues to be on tour and then kind of started thinking about, well, what does that look like across the country?

Like what places are telling the story, which places are running from it, and which places are doing something in between. And ultimately spent four years traveling across the country and across an ocean to try to answer that question.

Well, I want to stick with, uh, new Orleans or Louisiana and the Whitney plantation.

Um, what made you decide, uh, to go to the L to the Whitney plantation? It’s a fascinating part of the book and I want to start there. Um, and the fact that. It’s a plant it’s, uh, the Whitney plantation is sort of a site of slavery that is, um, sort of devoted to, uh, preservation of the way in which enslaved people actually live.

And what are some of, sort of the paradoxes of that, uh, including who now owns, um, the Whitney plantation. I thought that was a fast. I truly fascinating

story. Yeah. You know, the Whitney’s fascinating. Uh, and I was drawn to it in large part because it’s only an hour away from new Orleans. So it’s only an hour away from where I grew up.

And it’s surrounded by a sort of constellation of plantations where people can. Ha hold weddings and ceremonies and celebrations. And, you know, I was talking to a group of wedding planners who talked about how some people who hold wedding, their weddings in these, these different plantations across Southern Louisiana still use the slave cabins as bridal suites.

And so, you know, it’s, the Whitney exists as part of this. Ecosystem of places whose sensibilities and whose, uh, cured curatorial processes to the extent there even is one are, are animated by a different understanding of history. Um, and the story that those places tell about themselves, if they’re even telling a story about themselves, uh, historically.

Is, you know, centered on what I imagine, you know, many people who’ve been on plantation tours have experienced, you know, the, the sort of architecture of the big house and where the, the China was imported from. And, um, you know, the, the beauty of the land and the structure of the columns and the, uh, the core of the windows and, and all of these things that sort of sidestep.

You know, proactively ignore, uh, the people who often built these homes and the people who often served in these homes and the enslaved labor that made these estates possible. And so the, the Whitney instead is a place that, that rejects the idea that a plantation can be understood as anything other than an intergenerational side of torture.

And yet we should, while we should acknowledge that these places are intergenerational sites of torture. And capitalistic exploitation. We also have to lift up the humanity of the people who were subjected to this torture. So it’s a sort of both and where we recognize that. The whore of the institution, but also recognize the humanity of the people who were subjected to the harm of this institution.

And so it’s a place filled with, you know, the narratives, first person narratives of enslaved people. Uh, it’s a place in which we are regularly confronting, uh, the names and the, uh, and, and statues and faces of. Uh, people who, who were enslaved, you were thinking you confronting, uh, the, the idea of children being enslaved.

You’re confronting the idea of, uh, the specific and insidious kind of violence that women were subjected to under enslavement. And, you know, as I write in the book, it’s a place that is. In some ways, uh, an experiment that is attempting to it’s a hammer attempting to unbend four centuries of crooked nails.

And, you know, it’s not perfect in the way that, you know, no museum is perfect, but, but I admire it in part because it is attempting to do something in an environment, um, where that is. Hardly ever, you know, it is the only plantation museum in Louisiana that focuses specifically on slavery. And one of the only plantations, you know, one of maybe a handful in the entire country that do so.

Um, and I think that it’s important to have spaces like that, to lift up how exceptional they are and then to analyze how unfortunate that they are as exceptional as the.

And let’s juxtapose the Whitney plantation in Louisiana. And you do this in the book of the chapter that follows is on Angola prison and Louisiana state penitentiary, 18,000 acres, a former plantation turned into a maximum facility.

Uh, prison. And, you know, I’ve read a lot over the years on Angola, including, um, folks who are former black Panthers and black radicals who were sentenced to Angola folks who became politicized in Angola. Uh, but I thought it was really a striking, um, sort of on the ground experience, including with somebody who’s a foreign.

Um, formerly incarcerated inmate in Angola, who, who, who you have a dialogue with, um, during parts of this chapter. So let’s talk about Angola prison and the fact that, um, to this day, you still have, uh, folks picking cotton. And I mean, working on there, like if it was, you know, during the antebellum period of racial slavery, it’s really extraordinary sort of you go into sort of a time machine and you, you, you write a.

Traveling on I 10 west from new Orleans and, uh, for our listeners out there, I think this is a great book that shows us how important Louisiana is to American history and to global history. I think in a lot of ways, obviously for us academics, Walter Johnson has done this with soul by soul, but I think in a popular way, it’s going to be.

Um, and this book that does it for Louisiana, because just the number of eyeballs that are on this book is going to be it’s innumerable. So, um, let’s talk about that Angola and. That deep history that really continues to this day. It’s a very moving

chapter. I think. Thank you. That’s kind of you say, um, yeah, I mean, as you alluded to it’s a and goal is 18,000 acres wide bigger than the island Manhattan, the largest maximum security prison in the country, a place where 75% of the people held there are black men.

Over 70% of them are serving life sentences. And as you mentioned is built on top of a former plan. But what I always tell folks is that if you were to go to Germany and you had the largest, maximum security prison in Germany, and it was built on top of a former concentration camp, in which the people held there were disproportionately Jewish, that place would quite rightfully be a global emblem of antisemitism.

There’ll be a horn. It’ll be disgusting. We would never allow a place like that to exist because it was so clearly run counter to all of our moral and ethical, sensitive. And you’re here in the United States. We have the largest, maximum security prison in the country where the vast majority of people are black men serving life sentences, work in fields of what was once a plantation.

Many of them sentences children, many of them sentenced by non unanimous juries, which has since been rendered unconstitutional, but let’s, it’s prerecorded, the United States who are working in these fields, picking crops while someone watches over them on horseback with a gun over their shoulder. And so part of what I’m thinking about when I go to the Whitney or what are the ways that a history of white supremacy down only an X physical violence against people’s bodies, but also collectively numbs us to certain types of violences that in another global context with so clearly be unacceptable.

And what does it mean? Not only that that place is an interested in interrogating its relationship to this history, but that this place has a gift shop and in the gift shop, you can buy. Coffee mugs and shot glasses and baseball caps and hoodies and t-shirts and stuffed animals dressed in prison attire.

And, you know, on some of the paraphernalia, like on a coffee mug, for example, you can, uh, there’s a silhouette of a Watchtower and above and below the Watchtower, it reads and goes. A gated community as if to make a mockery of, or, and belittle the experiences of the thousands of people who remain incarcerated there.

The tens of thousands of people who have been incarcerated there, if not hundreds of thousands of people who’ve been incarcerated there over the course of generations. And so I think about the scholar city of Harmon and how she talks about the afterlife of slavery and the way that the history of slavery.

Shapes our social political and economic infrastructure and, and the way that it very directly and very clearly shapes our carceral infrastructure. And I think that is important because it’s not to say that mass incarceration and slavery are the same. They’re not they’re phenomenologically distinct entities that should be understood and analyze and interrogated on their own cruel terms.

Uh, and each of them has a cruelty embedded into the institution that deserves the precision of that specific type of analysis. But we can be clear about the way that this history is still incredibly present. In this, in this place and continues to shape it. And I think about the conversation I had with Norris, who’s the man who served almost 30 years and didn’t go Lou, who I spent time with on my, my time on my visit there.

And, you know, I’ve known and I’ve known Norris for a long time. He’s done a lot of organizing, uh, work in, in and around new Orleans and Louisiana around prison reform and was part of the group of formerly incarcerated folks who, who have led so many. Uh, efforts that have, uh, really, you know, made it so that the prisons that were, you know, Angola, you know, wants the most violent prison in the country.

And, uh, it is still a horrific place, but, but it is, you know, in a relative sense, safer for the people who are there then than it was before. And I was with Norris there. And Norris and I are on a bus and we’re, we’re leaving after our, our tour of these different parts of the prison. And we see in the distance, these men who are, who are working in the fields and someone is watching over them on a horseback and a gun sits across their lap.

And these men are lifting the shovels into the air and digging them into the earth and lifting these spades into the air and digging them to the earth and lifting these garden hose into the air and digging them into the earth. In order to, it looks at the men and he looks at his hands and his hands are covered in these cracks and calluses and scars from all his years, working in these fields.

And he’s like, Clint, I can’t explain to you what it felt like to work in cotton fields like picking cotton for 7 cents an hour in the same fields. Where for all I know my ancestors might’ve been picking cotton 200 years ago. And so for the people who are incarcerated and, and Gola, they feel what what’s the department talks about.

And they feel that afterlife of slavery in their bodies, right? Like it is, is as I talk about in the book, like there’s no need for metaphor because the land makes it literal. It is there, they are still on that land. And what are the failures of our, our collective public consciousness and our, our public memory around this institution that allows this prison.

To exist on this land, much less exist at all in the way that it does. Uh, you know, I could have written a whole book about just my experience at, at Angola, um, and, uh, Because there’s so much to unpack there. I’ve been working in prisons and jails for the last several years in Massachusetts, during grad school, and more recently here at DC jail.

Uh, but, but nothing could have prepared me, um, for. Standing in the execution chamber at Angola visiting death row at Angola spending time in the red hat, cell, black witch, uh, Albert Woodfox, you know, who spent, uh, I think more than 40 years, um, in solitary confinement and Angola writes about, so, so movingly in his, his, uh, national board national book, award finalist book, uh, solitary, which I highly encourage everyone to, to read, uh, Yeah, it’s, it’s a, it’s a strange and haunting and, and profoundly unsettling place.

Now the first chapter, which is a Monticello plantation, I don’t know if that’s a Monticello Monticello, but you’ll let me know how to really pronounce it. I found this fascinating. This is a very, I thought cinematic chapter and I would tell, um, listeners and potential readers. And even people who’ve read, it would just are interested in the conversation that this was a chapter that I’ve found.

Um, I won’t say funny. Ha ha. But it was very, um, you, you, you, you display a lot of good humor, um, in a very cinematic way. I could see when I was reading this book and I’ve read it a couple of times now, but when I was first reading it, I thought this chapter was very evocative. And the way in which you are sort of this, um, avuncular guide, um, at times deadpan at times, uh, to, um, you know, different, um, basically white interlocutors who kind of.

C Monticello in the same way that you’re showing it to us and the deep history, I thought it was quite, quite very, very endearing. And I was thinking of Kamala bell and United or the colors, the thing he doesn’t see. And then, and I could see you when I was reading this. Um, and I’m sure this might be in the works already, but taking us on.

A multi-part series on your book. And I could see you taking us to Mazzella and talking to these folks and saying, Hey, let’s just, you know, let’s just talk about it. And we sort of know you’ve got this deep, deep wealth of knowledge, but you really give people the benefit of the doubt. And you’re interested.

You could see how you’re an educator and a teacher as well as a student. And you used to teach in high school, uh, prince George’s county, you know, Harvard, the whole thing, but you’re so. You’re very, very generous. You’re you’re listening, you’re taking their feelings seriously. Right. And some of it is funny sometimes even when people are trying to express denunciation, it’s kind of, it’s kind of a little too faint about Jefferson and Monticello.

So I want you to, uh, I want it to one, share that with you, which I think is terrific. Um, but I want to talk about my, because I think there’s a kind of. You, you let us see the horror, but there’s a kind of lightheartedness to it, which is very disarming pedagogically. And I think unbelievably effective. And I, as somebody.

Who’s also an educator and always trying to be a better teacher and student. I thought it was really, it gave me tips and, and, and sort of it’s, it’s, there’s a lot of patients since humility in this chapter and in the writing of the chapter as

well. I appreciate it. And you know, in so many ways, the. Th this book is an homage to the docents and the public historians and the guides that so many of these places who to my mind, like really embody that generosity in their work.

And, and part of the, you know, one of the guys I focus on in that chapter is a guide named David Thorson. And, you know, David has been working at Monticello for, for many years and. He served in the U S Navy, I think for maybe three decades before he became a guide at Monticello and he leads this tour focused specifically on slavery of Monticello.

And you know, if you go to Monticello now there’s the primary house tour. There’s the slavery of Monticello tour. There’s the Hemings family tour. There’s a sort of horticultural tour. There’s I mean, there’s all, Jefferson was such a multi-faith multifaceted person and, and Monticello is a place. Has so many different stories to tell that no single tour can capture, uh, in, in its fullness.

Um, the nature of, of what that space and who that man were. And so they have all these different tours. And I went with, uh, with David on the slavery of Monticello tour and, and it was a really, you know, for me, that was a moment where, you know, as a teacher, I was like, oh, this is like next level pedagogy. I mean, he’s so brilliantly and masterfully.

Outlined the sort of cognitive dissonance of Jefferson’s intellectual project, uh, and, and embark, and really revealed in ineffective ways, the hypocrisy and the contradictions of so much of Jefferson’s, uh, beliefs in. And, and I was on this tour with maybe a dozen other people, and there was two women, Don and grace, uh, who were on the tour with me.

And I could see them, uh, as, as David was outlining, you know, the. You know, decades of, of Jefferson’s transgressions, um, as, as an enslavement and I could see their faces, wilting and their mouth sort of hang a gape when David said certain things and I went up, went up to them after. And uh, I said, you know, I would love to hear how you’re feeling about what, what you just heard from, from what David shared.

And I’ll always remember. I think it was grace who was like, man, He really took the shine off the guy. She was like, you know, they’re sitting there like, yeah. And they’re like, I had no idea. Jefferson owned slaves. I had no idea. Monticello was a plantation. And, and mind you, these are folks who, who bought plane tickets, rented cars, got hotel rooms who came to the site as, as like a pilgrimage to see the home of one of our founding fathers to see the home of the third president.

And had no idea that he was an enslaved and no idea that it was plantation. And that moment was so important for me. I mean, that was, that was the first, it is the first chapter of the book and it was the first chapter of the book that was written. Um, And it was so important for me as a writer because, you know, I think in, in my world and in your world and in the sort of social and intellectual spaces we can engage in, you know, everybody’s like, oh yeah, Jefferson was a flavor.

And like, you know, Sally Hemings was the period, you know, had children by Sally Hemings and, you know, enslaved his own children. Like these are things that we we know, and I think we can take for granted or we can. Estimate how many other people are familiar with that information. And that moment for me was so important because it reminded me that there are millions of people across this country who really don’t understand the history of slavery in any way.

That is commensurate with the impact that it has had on this country. And, and, and

why is that? Why is that? Because I think that’s true, but what, what, I mean, your book delves into, but I want us to, yeah. What, what, why, why is that? Because we’re talking about critical race theory, assaults on education pedagogy.

K through 12 right now as we speak.

So, but why is that? I mean, I think there’s, there’s a bunch of reasons. I mean, part of it is that we have a sort of structural and systemic failure within our education system. Part of it is that we don’t really have a comment. Educational framework or a foundation given, you know, w different we’re different than them.

A lot of European countries where the curriculum comes down from, uh, from a national, you know, government or has made on a, on a national level, uh, you know, Thousands and thousands of different, uh, local entities who make decisions about what curriculums look like. And, you know, oftentimes it’s, it’s like school by school and classroom by classroom, and really depends on, on who the, who the teacher is or who the school board member is.

And I think we see that, uh, in a profound way right now. And then also, you know, it’s the, the effective effectiveness of the lost cause, you know, I mean immediately after the war, There was a sort of 19th century version of gaslighting that happened. And we see it happening in real time. Now with January six, right.

Where people attempt to tell us that something that we all saw isn’t what actually happened. And even though like we see the video, we see the photo, we heard the audio and they’re like, oh no, no, no, that’s not, that’s not what that was. And we see this. Or Wesleyan, uh, attempts to distort and, and, and create a sort of like fundamentally different epistemological realities so that we don’t our memory of this thing that happened less than a year ago is already being skewed and misrepresented manipulated so that you have millions of people who have different ideas.

What was happening, even though we know what happened. And this happened in, in, you know, right after the civil war, I think all the time about how Alexander Stevens, the vice president of the Confederacy in 1861, he makes his famous, uh, cornerstone speech or rather his infamous cornerstone speech, which he, in which he says the cause of the great rupture and this great revolution, uh, of, of the civil war.

Is slavery. He says it is, you know, this new nation is built on the belief that, that the white man is superior to the black man. It is that slavery is the cornerstone upon which this new nation will be built. And the goal of the Confederacy is to perpetuate slavery, uh, it as for as long as we can, because it is central to the Confederate project.

And then after the war, Robert Lee surrenders at Appomattox fighting dissipates out west, and the war is over. And people go to the Alexander Stevens after, and they’re like, wow, four years ago, you made this infamous speech, you know? And you said that slavery was the reason that the Confederacy was formed and slavery was the reason that the civil war was fought and African inferiority was the idea that a new, this new society was being predicated on what are you, what do you have to say for yourself?

And he’s like, I never said that. And everybody’s like, what are you talking about? We were there. We saw it. We read in the papers. We every, we documented it and he’s like, no, no, no, you must be mistaken. I never said anything. I never said anything like that. You must have misquoted me. And so immediately after the war, we see this happening from people who held some of the highest positions in.

In the Confederate army and part of what I outlined in the book specifically in the, the Blandford cemetery chapter, where, which is one of the largest Confederate cemeteries in the country, where the remains 30,000 Confederate soldiers are buried. And I spend the day there with the sons of Confederate veterans.

And that was going to be a question.

What, what, what, what made you go to bland for it? That was going to be a question, but had you ever visited a Confederate Memorial before this, in terms of an actual grave site before?

I have never even considered going to a Confederate grave site? I mean, I think, and one of the things I like about being a writer is that it pushes me to do things that like.

Like the regular black dude walking down the street would not do like, there’s no context in which, um, I wake up and I’m like, I’m going to go spend Memorial day with the sons of Confederate veterans and the United daughters of the Confederacy at a enormous Confederate burial ground. But Clint, the writer is like, oh, you have to go.

Right? Like it might be strange. It might be unsettling. It might be dangerous. What data ended up being was also incredibly clarifying. And this kind of brings those to these two questions you have together where it’s like I went there and I remember speaking to a guy named Jeff who was a member of the sons of Confederate veterans.

And. And Jeff was telling me about how, when he was young, his grandfather used to bring him, uh, to the cemetery and they would sit in this gazebo and that sits at the center of the burial ground. And they will come at sunset and they would watch the sunset and his grandfather would sing him the old Dixie Anthem and they would sing it together.

And his grandfather would tell them these stories of men who were buried in these fields and how. You know, this war wasn’t about slavery, how it was really the war of Northern aggression and how, uh, you know, these are people who fought to preserve their culture, who fought to preserve their family, who fought to preserve the south, who fought to preserve their communities.

And now Jeff talks about how one of his, his favorite things to do is bring his granddaughters. And he says, I love walking through the grave site with them. I love telling them the stories. My grandfather told me, I love singing the songs to them, that my grandfather sang to me. And this is how the story is passed down.

This is how it’s perpetuated. And so the thing is, if you go to, if you go to Jeff and you’re like, Jeff will actually, you know, the, the Confederacy was very explicit about why. Succession happened about why the war would be fine. I mean, all you have to do is look at the declarations of Confederate secession in 1860 and 1861 that each of these states created as they were succeeding, uh, at the secession conventions.

And you know, you have a state like Mississippi in 1861 that says our position is thoroughly aligned with the institution of slavery, the greatest material interest in the world. And so they’re not, they’re not vague about why they’re succeeding. They’re quite clear about it. Alexander Stephens was clear about it in his speech.

They were clear about it before the set, when they were trying to prevent the south from seceding, by creating the Crittendon amendments, which basically said, okay, if you stay and don’t succeed, we won’t ever touch slavery. And ultimately, and thankfully it failed, but, but everybody was clear that slavery was the cause of all of this.

And so we have all this primary source evidence. We have all these documents, we have all this empirical evidence, but for, but for Jeff, it doesn’t matter. Right. Cause for so many people, history is not about primary source documents, not about empirical evidence. It is a story that people tell, and it is a story that they have been told.

It is an heirloom passed down across generations. It’s something in which loyalty and family and lineage take precedence over truth. And so if Jeff has to accept this information, even with the robust contemporaneous documentation that exists. He would have to, it would, it would disintegrate so much of who he is understood his grandfather to be, because he would have to confront that his grandfather lied to him.

And when you confront and when you have to reckon with the fact that. If somebody you love, might’ve lied to you. You have to think about what else they might’ve lied to you about. And that sort of threatens to crumble the foundation upon which your relationship with that person is built. And if your relationship with that person is central to who you are, who you are as a person, then it becomes not only a sort of inconvenient need to reassess and recalibrate our relationship to American history.

It’s like an existential crisis. It is because your sense of who you are is so deeply tied to the myths that have been perpetuated the myths of undergirded, your identity and your sense of self. And so if it isn’t, if people are selling, sharing different information, if there is a shift in our public consciousness, as there has been over the past several years and then supercharged with George Florida a year ago, And then you have millions of people.

You know, the sons of Confederate veterans are the most extreme version of this. But I think part of the thing that we see with CRT is that it has become this boogeyman. That is a direct response to. The shift in public consciousness that has happened over the course of the black lives matter movement because of the work that activists and organizers and writers and scholars and journalists and folks have done to, to shift us away from the, or to, to rather expand our understanding of, of this country and its history.

And now you have many people who, who sense of. Who they are, is under threat, who sense of their community is under threatened. So that’s a long way of saying that, like, you know, this goes back to the original question you asked about, well, why, why is it it’s because when you begin to tell a more honest and fuller story of American history, there are many people who have to tell a different story about themselves.

And there are a lot of people who were very scared to do that, because then it calls into question the things that you have and the power you wield and the opportunities you’ve been given. And you have to assess in a fundamentally different way, why you have those things and why so many other people, don’t it.

Disabuses you of the myth of meritocracy disabused as you have the American story, that if you simply work hard, everything will work out for you because we know that. We know it sociologically, we know what empirically we know it historically. And as soon as that began to more fully infiltrate, the sort of larger American public consciousness, and then you saw this effort to say, actually, we don’t need to.

Tell a story, you know, we don’t need to tell the different story about America. Let’s keep telling the story that we were telling,

because so far that’s worked out so great. Um, so Clint, I live in Texas and Austin, Texas, and you have the chapter on Galveston island and Juneteenth. And, um, this book came out right around the time that, um, then, you know, June 10th became a holiday, but while you were writing it, you couldn’t have known.

Let’s talk about Galveston and really also wall street too, because I think those chapters are very interesting because they tell different parts of his story. The Galveston story Juneteenth, which has now become a federal holiday, really tells the story of, um, emancipation day independence day. But there’s also tragedy that happens in the context of that.

Right. So it’s that, it’s that, uh, sort of there’s black joy. You know, um, uh, that are intermingled in that sense, but it’s, it’s still a very, very important story. And then the story of wall street, you know, you say, you know, we were the good guys, right. Really up in the nations, um, narrative about itself because you see how, uh, you know, all these black souls help build.

Uh, lower Manhattan. They helped build up wall street. They were, there were enslaved people there, there were free people there, there were black people there. Black bodies have everything to do with what happened in the north and the supply chains of slavery, power and privilege for some and grief and misery for others.

So I wanted to, um, talk about that because I thought those two chapters, which are the last two chapters before this final chapter. On on Goree island and the car said off of the car Senegal, um, and then the epilogue with your, with your grandparents that are set in the states that are set in, in, in the United States before you go global, but this Galveston got visited Galveston yet it made me want to visit.

I’m going to take my daughter and take the family there. So it made me want to, um, want to go

there. Yeah. I mean, Galveston was a it’s interesting, cause I, I went to. Galveston for Juneteenth? Uh, probably I think that was less than three weeks after I left Lanford. Um, and so it was this fascinating juxtaposition because at, uh, Blanchford I’d spent this time with the sons of Confederate.

And when I got to Galveston, uh, part of the commemoration of Juneteenth included the sons of union veterans. Um, and so, you know, it is this, it was this really remarkable, uh, event. Uh, and, and this was before Juneteenth became sort of national phenomenon, uh, in the way that it is now, certainly before it was a federal holiday.

And I’m, I’m glad I was able to go. Before, you know, I don’t, I don’t want to say that it was more organic or more, but, but it was, it was still relatively under the radar. Um, and so I, I appreciated the opportunity to go when it was, it was a large event, but it was still intimate. Uh, and, and you were spending time there with people who’ve lived in Galveston for generations, people who are likely to dissent.

Of the people who, who benefited, uh, directly, um, from general order, number three, uh, may by a union general Granger, uh, that, that all slaves were free, that the civil war was over, uh, that , that, you know, Robert Lee had surrendered mathematics two months before the emancipation proclamation had been. Put into effect over two years before, and suddenly you have union soldiers coming into Texas.

Uh, many of whom are black union soldiers who are now letting the 250,000 people in Texas know. That they are free. And this was one of the places where I spent a lot of time with the, uh, federal writers project, uh, slave narratives, which I hadn’t been really familiar with before I started the process of writing this book.

But for those who don’t know, it’s a part of a new deal initiative, um, between 1936 and 1938, uh, called the federal writers’ project. Did a lot of sort of oral history work across the country. And part of that was collecting the stories of people who had been born into slavery and who were still alive in the late 1930s.

And there were, there were thousands of these people they collected, um, I think over 2300 narratives and, and they, you know, these. Are inflected with, uh, their own limitations, because many of the people who did these interviews were, were racists. You know, uh, they carried their own biases. They often, uh, reflected, um, black speech in a way that attempted to sort of caricature black people.

Um, still, it is one of few resources that we have of enslaved people. Speaking or formerly enslaved people speaking for themselves about their experience. And so I used a lot of those, uh, specifically accounts of people from Texas in order to try to make sense of this. And you encounter regularly, you know, people who, who are like.

Um, you know, they weren’t, they weren’t told about it. And then their enslavers PR intentionally kept them from having access to that information because they wanted to hold onto this lease for so long. I mean, these are people, many of the enslavers in Texas or people who were in slavers in Virginia and South Carolina, North Carolina, and they fled once the union army had taken over those places and they came to Texas so that they could keep their enslaved property.

Um, And, you know, I think more generally for, for me, Juneteenth brings up, it is both a, um, a day to celebrate the end of one of the worst things this country has ever done. And to mourn the fact that it took as long as it did. And I think it also is a space that reminds me that, you know, black people came to this country.

Uh, or enslaved black people came to this country 250 years ago or to the British colonies that would become this country. And from the moment in sleep, people arrived on these shores. They had been fighting for freedom, but freedom did not come until 1865. And so what that means is that the vast majority of black people who fought for freedom, never got a chance to see it, but they fought for it anyway, because they knew that someday someone.

And that like, well, you and I are able to sit here and have this conversation only because of people who fought for something that they knew they might never see, but who fought for it anyway. And I think about what sort of responsibilities that bestow upon me does that puts it upon us to try to build the sort of world that, that we and our children deserve to live in.

But. We might not see ourselves. But part of what we have to do is to do the work that other people have done for us is to, you know, we might not experience the fruit of our labor, so to speak, but, but we know that someday someone will, and we are all sitting here sort of chipping away at this. And this wall, um, and we don’t know if the wall is six inches thick or 600 miles thick, but you know, the more you chip away at it, the less people who come after you have to chip away at.

And at some point somebody is going to get to the other side of that wall and going to see that light. And so, you know, that is that’s part of the black intellectual project. That’s part of the black, the project of, of a black lineage. Like that is the tradition that we’re a part of. And I think the Juneteenth embodied.

Embodies that right. That, you know, we are still pursuing this thing that, that we don’t know that we will ever see ourselves, but, but we are part of a lineage of people who have pursued it anyway. And so that’s what we got to do. And how does New

York city changed this story? Because in a lot of. I thought your New York chapter was similar to, um, it reminded me of the 16, 19 project, and I now just have the hard cover book.

Um, and that’s very exciting, but just New York city and certainly the story we tell ourselves about slavery and racism, New York city, doesn’t figure into that story historically in a wall street. You have here in the New York city chapter, you also talk about, um, the statute of statue of Liberty’s origins and, um, abolitionism as well.

And those chains are really, you know, I’m with you. I think those chains are really meant to be, you know, uh, racial, slavery, breaking the chains of racial slavery and not just sort of, you know, immigrants coming from unfortunate backgrounds. So I think the New York city. Chapter is very interesting and it really forces us.

If we implicate New York in this history of racial slavery, it really forces like you were saying earlier in the conversation, people are going to have to change how they think about themselves. And in that context, it, it forces people who might be called northerners, Yankees, progressives to think about their own culpability, both Ben and now, uh, in these systems of racial oppression and subjugation

it’s New York.

For me, I was cognizant of the fact that my book might be one that. That people who have not necessarily read sort of some of the academic histories on, on slavery might, might encounter. Uh, and so part of what I wanted to do was, you know, if this book was going to be an entry point to the sort of larger historiography on slavery, I wanted this book to, to quickly disabuse people of the idea that, uh, it was something that, uh, was that only existed in the south.

And. You know, I wrote this chapter about New York, but I couldn’t rip, I could’ve written about Boston could have written about Providence, could have written about new Haven, could have written about Detroit as, as time miles is so, so wonderfully done. And part of what it was was also, and so much of this book was a desire to fill in the gaps of my own lack of understanding and New York.

I think on a surface level I knew was. Was I, I was like, I knew slavery existed there. I knew it was complicit in the larger project to slavery, but I didn’t know in, in a deep way. And so I spent a lot of time with the work. I read Berlin a lot of time with the work of Leslie Harris specifically, whose incredible work on this is illuminated.

This, this history has shown that, you know, New York city was the second largest slave market in the. Uh, after Charleston, South Carolina for an extended period of time, that the mayor of New York city Fernando would in 1861, actually proposed that New York city succeed from the union alongside with the states of the Confederacy, because new York’s political and economic and social interests were so deeply entangled in the slave ocracy of the south, you know, or there’s as you alluded to that, the statue of Liberty was originally.

As a gift and proposed to be given to a gift to the United States, by a guy named Eduardo , who’s a French abolition, a French abolitionist and a constitutional expert. You know, that, that it was originally meant to be given, to celebrate the end of slavery. And over time its meaning shifted and changed and uh, and was distorted and, and they physically moved, you know, the original design had lady Liberty holding, broken chains and one of her, one of her hands, uh, and they moved those to under.

And I tell people that, you know, there was a moment where I was standing next to the statue of Liberty, which, which is also just enormous in ways that I hadn’t fully, fully understood. And I was standing next to it. And these chains are like, sort of snaking under her robe and you can see them on her feet, but you can only see them from an aerial view, like from a helicopter or from a plane, uh, or from some talking about from somebody taking a photo, you know, from a helicopter or plane and.

There was this moment where I was like, standing, you’re standing next to the statute, but you can’t see those change. And it’s, and it’s this kind of metaphor, uh, almost, uh, you know, two on the spot of a metaphor for how the history of slavery is like hidden in plain sight, how it exists right next to us.

And sometimes we don’t even know, you know, cause like all the times I’ve seen images of the statue of Liberty all the times. I’ve, you know, heard about the statue of Liberty, read about the statue of Liberty. I never know. That had never been part of the story of, of that statue of the statue of Liberty that I’ve been told.

And I think that that’s a microcosm for the story of this country, right. That it’s so central to this country’s existence. It’s so peripheral to the way that we are often taught American history. And so

I’ll my I’ll close with my final chapter. I wanted to my final question. I want it to talk about Africa, but I really wanted to talk about your grandparents too.

So if you could somehow still talk about Goree island here I’ll I would welcome it, but I was so moved by your, your, your talks in the epilogue with your grandfather and your grandmother. I have one line from page 2 86. And you and your grandmother have gone to the national museum of African-American history and culture.

And she says it was really depressing, very depressing to see that. And I had a hard time even now, trying to accept the fact that we can be so cruel to one another. It’s just so inhumane, looking at the slavery as it existed with the chains around your neck, hands. You can’t go to the bathroom. That was really real.

So it was very, very depressing. Um, and then you asked her about the parts that were specific to Jim Crow segregation, and she keeps telling you I live this. Um, so I thought that was incredibly moving and really wrapped a nice bow and the entire tire book and the entire project to just to show how multifaceted and multi generational.

And complex. This

all is. Yeah. I, you know, I think there was a moment as I was researching and writing this book and I was like, man, I’ve asked all these strangers, you know, hundreds of strangers, people I just met and might never see, again, all these questions about the sort of give me portraits of their lives and all these intimate questions about their life histories.

And I realized that I had never been as intentional with my own family. As I had been with these, with these groups of. And I kind of decided I needed to change that. And so, you know, as you mentioned, I was walking through the museum with my, my grandfather born in 1930, Jim Crow, Mississippi, and my grandmother born in 1939, Jim Crow, Florida, and was thinking about, you know, how so much of the history that is documented in this museum.

So I went to the violence that is documented in this museum. Are things that my grandparents lived through firsthand. And as you said, like, my grandmother had this refrain. She was like, I lived it. I lived it. I lived it. And I think often about the, how this book was meant to convey a sense of our collective physical proximity to this history and how the scars of slavery are etched into the landscape all around us, but it also in doing so I think it gives us a sense of our temporal proximity.

To this history. And when I think about the national museum of African-American history and culture, I think about Ruth Bonner, who is the woman who opened the museum in 2016, alongside the Obama family who rang the bell to sort of signal the opening of this museum. And she was the daughter of an enslaved person, not the granddaughter, not the great granddaughter.

She was the daughter in 2016 of someone born into chattel slavery. My grandfather’s grandfather wasn’t. So I think about my four year old son sitting on my grandfather’s lap. And I imagine my grandfather is sitting on his grandfather’s lap and I’m reminded again that this history we tell ourselves was a long time ago truly was not that long ago at all.

And so the idea that this, uh, you know, that this history. It would be considered irrelevant to the landscape of, uh, of, uh, contemporary racial inequality is revealed to be morally and intellectually disingenuous. And so I hope that, you know, among other things, what people take from the book is as a sense of our collective proximity to this history, that it’s are only a few generations removed from this, that there are people alive today who, who were raised by who loved, who were in community with.

People born into chattel slavery, and it shapes what our society looks like in, in profound, uh, still subtle ways. Um, and, and we have to be cognizant of that.

Well, brother, this has been a pleasure. You know, we’ve been chatting with Clint Smith, who is a staff writer at the Atlantic author of a poetry collection, counting descent, award, winning scholar and writer and poet.

And he’s the author of the New York times. Uh, number one best seller, how the word is passed a reckoning with the history of slavery across America. Um, I absolutely, um, highly recommend this book. It’s a great read in addition to being, um, so illuminating, it’s the kind of book, um, I’ll be teaching in my graduate seminars.

Um, you know, and, and people are going to be reading and talking about and debating for, for generations to come. So, uh, Clint, thank you so much for talking.

Thank you. This has been, uh, been a real pleasure. Thanks

for listening to this episode. And you can check out related content on Twitter at Peniel Joseph that’s, P E N I E L J O S E P H.

And our website CSR D dot LBJ dot U texas.edu. And the center for study of race and democracies on Facebook as well. This podcast was recorded at the liberal arts development studio at the college of liberal arts at the university of Texas at Austin. Thank you.