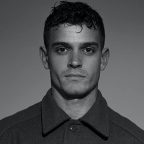

Dr. Eric Cervini is an award-winning historian of LGBTQ+ politics and culture. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College and received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Cambridge, where he was a Gates Scholar.

As an authority on 1960s gay activism, Cervini serves on the Board of Directors of the Harvard Gender and Sexuality Caucus and on the Board of Advisors of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of gay American history. His award-winning digital exhibitions have been featured in Harvard’s Rudenstine Gallery, and he has presented his research to audiences across America and the United Kingdom.

He lives in Los Angeles with his two plants, Coco Montrese and Fig O’Hara.

Guests

Eric CerviniActivist and Award-Winning Historian of LGBTQ+ Politics

Eric CerviniActivist and Award-Winning Historian of LGBTQ+ Politics

Hosts

Peniel JosephFounding Director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin

Peniel JosephFounding Director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin

[0:00:07 Peniel] Welcome to race and democracy, a podcast on the intersection between race, democracy, public policy, social justice, and citizenship.

[0:00:21 Peniel] Well, we are very pleased to have with us for this podcast. Uh, really a stunning new author and scholar and activist, Eric Cerveny. Dr. Eric Cerveny, who’s just come out with The New York Times bestseller The Deviance War, The Homosexual versus the United States of America. And Dr Eric Savini is an award winning historian of L G B. T. Q I. A. Culture and politics. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College and received his PhD in history from the University of Cambridge, where he was a gate scholar. The deviants War is his first book, and you can catch Eric on his fabulous podcast, the deviants world. So, Eric Cerveny, welcome to race and Democracy.

[0:01:08 Eric] Thanks so much for having me.

[0:01:10 Peniel] Uh, this is really a next ordinary book I learned so much while reading this book and really the fact that this book came out in 2020 in the spring of 2020 when there has been the largest social justice movement, racial justice, movement, but really intersectional justice movement in American history. I think really speaks to just how current this book is, even as it looks at really the history of the gay rights movement. Um, from the perspective of Frank, a comedy who I really had not really heard of. I knew about the Mattachine Society. But you do such a great job through 20 chapters of weaving, Um, this astronomers tail and how that tail really helps to change the United States in a lot of ways, change the entire world. Eso I wanna just start at the beginning because in the acknowledgements you talk about how you discovered Frank Comedies Papers in 2005. Know what inspired you to write this book? It’s such an important on Dwell Executed a dazzling first book. What inspired you?

[0:02:25 Eric] Oh, thanks so much. Well, I discovered Frank’s name as an undergraduate, and, you know, I had gone to college thinking I wanted to go to law school, maybe work in public policy or government or something like that, and then happened to take my first history class on the history of American populism, and my mind was blown because realizing how much of history had not been taught in my you know Round Rock, Texas Public School Onda How much history was still left to be told on DSO around that time. I happened to watch the film milk about Harvey Milk and in the city supervisor in San Francisco, who was assassinated tragically in late seventies, uh, and similarly was just completely blown away and and, frankly appalled that I hadn’t heard his name before. And I had just come out of the closet, you know, a year or two prior to that. And it got me to thinking what other figures in our past have also been erased from the textbooks? Uh, figures like Frank Kameny, who, you know, historians have have long regarded as the grandfather of the gay rights movement. But until the deviance war, there hasn’t been a book about it. On DSO, I went down to the Library of Congress, still has an undergraduate on, opened up his his personal papers one of the largest collections of LGBT activists in the world, and realized that this was truly that the hidden history of gay rights in America. And that was seven years ago. And now Master’s and PhD and book later here we are now.

[0:04:12 Peniel] When I read the deviants war comedy, he comes off to me as somebody who is both militant, at times, even radical. But then over time you show how there’s this sort of push pull factor, this tug of war both within the Mattachine Society, the daughters of Librettists three. Gay Liberation Front, where at times he’s leading. But at times he’s really forced to follow. So I wanna talk about the arc of his career, how his activism really allows these other sort of tributaries to flow into these different directions that at times outpace um, his radicalism.

[0:04:57 Eric] And I think that’s something that that, you know, we, as historians, recognize. But sometimes in especially storytelling or in Hollywood, it’s easy to forget that, you know, people change and they have character development or changes in there political beliefs or ideology. But so does the world around up. So does the country, And I think you’re you see it so clearly, you know, especially in your own work on Carmichael and, um, this book on comedy when you’re talking about the sixties in a decade of such turbulence and change, when society is changing at such a rapid pace, around you. It’s easy for your own beliefs to get eclipsed into become outdated even though you were once ahead of the curve. And I think that’s something you see with Frank Kameny and you know I identify him is is really the inventor of what we now know and celebrate as gay pride. What we celebrate each and every June on DSO that in 1961 to declare that to be gay was a moral good and to make that argument in a Supreme Court petition and to do so publicly, Aziz, your your authentic self. That was a very radical act. But then, by the mid sixties, you start to see, actually, that’s kind of the bare minimum of of what you have to declare to be a part of the movement. And you have a new generation of activists, uh, inspired by people like Stokely Carmichael inspired by black power, saying that that’s not enough. We need our own organizations, our own self-determination, um, and our own political power. Uh, and it’s no longer enough just to be fighting through these old traditional respectability laced means.

[0:06:52 Peniel] Now, before we get to the real radicalism of the GLF and these other groups, I want to talk about comedy and how one of the things you do really, really well, especially in the books first half when we’re being introduced to him is we really get a sense of who he is. He’s like this brilliant gay man who gets a PhD serves in the Second World War, becomes one of the few astronomers in the United States. But then he’s also as a gay man, subject to unbelievable government surveillance and intrusion and just discrimination on outright violence and blackmail by local police in Washington, D. C. By police everywhere. But also when you think about the Department of Defense and not having your security clearance, so you do an extraordinary job of really bringing us into the world of being a gay man in the 19 forties and fifties. You’re looking here at a largely white population, and we’ll talk about race further, but it seems pretty terrifying right here. When I when I saw on some levels what gay men had to go through, and at times gay women, lesbian women, but they also resist. They buy houses, they do house parties they do dance parties. You have a very poignant scene where one young man is crying and saying he’s never seen so many handsome men together, just dancing. So it’s really an extraordinary and very poignant. I could I could visual ise it while reading. And we’ll talk about the movie. You know? I’m sure there’s a movie. We’re gonna talk about that, Erica, that has to be in the worst. Is this an extraordinary book? So, tell tell us about that. Tell our listeners like What was it like being gay for, to be Frank Kameny exploring, trying to explore your sexuality, knowing that there was nothing wrong with you. But there was something awfully wrong with the society. What what was that like?

[0:08:50 Eric] That’s well said. And I think that’s something that Frank Kameny, what made him so different was that he was able to recognize that that it wasn’t his own sexual orientation or his own condition that May that was the issue. The issue waas society and its inability to accept difference and it except nonconformity. But you’re completely right. I mean, it was absolutely terrifying to be not just nonconformist but a sexual nonconformists, a sexual deviant in the fifties and sixties. And for a bit of context. You know, a lot of people have heard of Joseph McCarthy and the Red Scare and the purges of alleged communists and and security risks and the government in the fifties and sixties. What they don’t realize is that it even higher rate. Uh, the government was systematically persecuting, dismissing and labeling, uh, and marking as forever a sexual deviant. Anyone who was discovered to be a homosexual who works for the government. So someone like Frank Kamani you mentioned he was an astronomer. He got his PhD in astronomy in 1956 just months before the launch of Sputnik in the beginnings of the space race. So you quite literally could not have picked a better time in a better profession, uh, in all of America than to be, you know, someone who is an expert in space at the very beginning of the space race on Dyear, yet Onley months after he started his job at the Department of Defense, helping develop some of the systems for missiles and space rockets, uh, they found out that he was gay. And after a series of humiliating interviews. He was fired and then banned from working for the federal government or in the aerospace industry because it required a security clearance for the rest of his life. And people at the time knew that this was a risk. And that was something that any time you entered ah, gay bar any time you went to a public restroom, maybe in the y m c A, um, anytime you held another man’s hand, um, you were at risk of first being arrested for either vagrancy or lewd conduct or loitering any number of different offenses you could have committed. But the worst part was after that arrest. First, your arrest would be forwarded to the FBI to ensure that you did not work for the federal government so that you could be systematically removed from your post. Second, uh, your arrest would go to the media to the newspaper, which would regularly report on your full name and your address of any perversion arrests that it occurred and then third, the Police department, often informally, would call up. Your family would call up your employer and say, Did you know that a pervert is in your family? or is working for you. So there was a multi layered system of persecution that existed from the local level to the federal level that essentially created a caste system in America that, you know, of course, was over laid the racial caste system. Eso to be someone like Beard Rustin where you had to grapple with those both parts of your identity wasn’t even scarier prospect in 19 fifties and 19 sixties. And so it really was a time of fear. But what made Frank Kameny so different was he was the first actually like that.

[0:12:25 Peniel] Now I wanna we’re gonna talk about civil rights in a second. But before I get to that, there were two figures that really stood out. And I want to talk about Randy Wicker and Warren Scar very for a second. Who were they and why do they figured so importantly in this narrative?

[0:12:43 Eric] Well, I’m so glad you asked about Randy Wicker, because as someone who’s from Austin myself and is a big Longhorn fan, he was a University of Texas undergraduate, uh, in the late fifties and graduating in 1960. He was essentially an openly gay student, not to the entire class, but within at the time, if you were out of the closet or that they didn’t really call it the closet yet. But if you had come out then that meant that you were you had come out into the gay world on it didn’t necessarily mean out to the public. So he was an outstanding Dent’s at the University of Texas, very much a part of Austin’s gay world. It had gay bars even in the late fifties on, and was also responsible for a few years later after moving to New York, organizing the country’s very first, uh, direct action for gay rights, UH, a ticketing demonstration outside an Army induction center in lower Manhattan. And so you see how wicker is looking at people like Rustin and King organizing and planning the march on Washington in 63. And you see within even the FBI reports who are keeping track of people like like Randy Wicker and Frank Kameny. Um, the reports of Oh, they’re planning on following the footsteps of Randolph and King and Rustin in finally marching as homosexuals for their own rights. And on the flip side, you have Warren scar Berry who waas. I think one of the most fascinating characters in the book on Doll, so elusive and enigmatic in that he was an FBI informant. Eso He was a gay man who was living in D. C and was recruited. Hey, actually, voluntarily went to the FBI offering his services to essentially spy on Frank Comedies organization, which was known as the Magazine Society.

[0:14:45 Peniel] And do we know why he did this?

[0:14:46 Eric] So I That was one of the things I was able to actually figure out by cross-referencing his name with, uh, Frank Kkamini’s personal papers on it was essentially an act of revenge. It seems like another member within the Mattachine Society and other activists, um, they had had a relationship. And then, um, I think there may have been an affair. And Warren Scar berry was so upset and intent upon, uh, ruining the life of his ex-lover that he walked into the doors of the FBI and gave over a list of 80 so names of of homosexuals in the D. C area, many of whose whose life, their lives were likely ruined. There’s no way of knowing, uh, but it certainly goes to show the extent to which the government will, uh, go to really ruin and persecute a marginalized group.

[0:15:45 Peniel] Now talk about comedy and his relationship and really the Mattachine Society as well, and the daughters of the biggest, the relationship between them and the larger civil rights struggle. Because I thought, What’s really interesting? When you get two chapters like The Alliance, you really start to look at the larger ferment that’s happening You look at I thought one of most fascinating parts of the book for me was looking at from the perspective of the gay liberation movement, the gay rights movement, John F. Kennedy and the Kennedy administration and June 11 63 when he does the civil rights speech and how there are all these plans and machinations and Medgar Evers gets assassinated here, what these gay activists are trying to utilize, and also how they try to utilize the march on Washington as as as something to buoy their own movement as well. And they all know who fired Rustin is, of course, eso tell me about Khamenei and the the civil rights movement, and also, you know, did you find really much interaction with African American gay activists and gay rights activists. What did they think of somebody like James Baldwin? In addition to buyer Rustin like So, were there were there times of interface or not?

[0:17:02 Eric] Well, those those are to really good questions because I think they show the answers. You wouldn’t expect them to be so different because to answer your first question, the chief roll off Frank Kamani and the Home a file movement, and I think that their greatest contribution was essentially toe act as a Xerox machine they took. Not just, you know, there’s been so, so much great discussion about how people of color, especially at Stonewall and in later years helped build our movement. But what I’ve been trying to show through this book is that it wasn’t just ah, single riot led by people of color that that contributed to the gay rights movement. It was every step of the way, uh, the gay rights movement or the home of file movement, as it was called before Stonewall was Xeroxing and borrowing from the black freedom movement on you can trace it all the way back, you know, to Montgomery on to see how, uh politics of respectability were used there in the selection of Rosa Parks to be the symbol. You see it in Greensboro with the very well dressed students you see it with, uh, you know, other activists being told to dress as if they were going to church before going on to the streets. And every step of the way you see the gay minority on very new minority borrowing the exact same tactics, especially of respectability. So Frank Kameny and Randy Wicker, when they protest outside the White House or the Army Induction Center, they have a very strict dress code, uh, stipulating that if you were a man, you gotta wear Ah, suit and tie. If you’re a woman, you gotta wear a dress on Ben. Of course, later years. This is still before stonewall. You have the development of black power, and black is beautiful. While that becomes gay power and gay is good. And that was the invention of Frank Committee. But he was borrowing from, uh, Carmichael. He was borrowing from the movement. He was very conscious that he was doing that. But on the flip side, you asked about kind of the demographics of the movement. It was overwhelmingly white. Uh, there was one instance I could find of a black person attending. Ah, machine meeting. And you know, I was researched. What happened? I was asking, you know what happened to, um, that guest who came to the meeting and the person I was interviewing said, Oh, well, we all assumed because he was black, that he must have been an FBI informant because all of our meetings to date had been full of white people, and so we were all very suspicious of him. And of course, he never returned. And you see other instances of essentially, you know it There was they were not immune just because they were also oppressed by the state, they were not immune to racism. And I think it’s one of the unfortunate part of the pre stonewall movement of just how exclusionary it was, but also how ingrained it was within segregated society within Washington. Because the gay world, especially justices it is now, was extremely segregated when it came to, uh, the bars when it came thio apartment, social gatherings, things like that. That, of course, were the product of larger structural issues. But I think the activists could have done much mawr to build official formal coalitions with the black freedom movement because you see opportunities that happening throughout the 19 sixties, Uh, in time and time again they fail. And so I think it really shows us now in 2020 how, as we are having a national conversation with gender issues and on racial issues once again, how important that intersectional fight really is?

[0:21:04 Peniel] Well, one of the things that you show with Kamani is how he responds, including, at one point running for Congress as the movement starts to get further radicalized because of black power because of the firm it of the late 19 sixties. So even I want to talk about Stonewall, of course, and and Marsha P. Johnson and others, and and they’re very interesting relationship between her and wicker that you describe. But what happens to really radicalized this movement, like what leads to stonewall and marching for pride and really saying, You know what? We’re not going to do the politics of respectability but really saying We’re queer, we’re here, gay is good, and we’re going to be part of this wider struggle for reimagining social justice in American in American society. What happens?

[0:21:58 Eric] Well, I think so many people, whether in the general public or even within academia, have studied stonewall in a vacuum, looking at really local issues of what may have prompted that uprising. And I think what’s really important. What I try to do in the book is to put it in the context of the 19 sixties, right violent uprising, violent resistance in the destruction of property had become a valid method of resistance increasingly throughout the 19 sixties. So, of course, you know, you have, uh, 67. You have Detroit 68. You have Washington and all over the country and then 69. Of course, you have Stonewall. So they’re once again were pulling from, uh, resistance in black communities. You have. You know, even in the book, you have people like Carmichael saying we need toe tear it down like this entire system is intent upon keeping us oppressed. And so we need to tear it down. And you have that same You have little inklings of it happening before stonewall. But really, what made that event so different was the media coverage. And I think any time I I have to explain to people why stonewall was so important, even though there had been violent resistance, uh, in rebellions and other locations before stonewall, uh, they didn’t have to. Members of the press, You don’t have to reporters from the village voice there, right? And I think you see it this June when, As soon as the resistance became violent, right, as soon as it became, you know, the riot police were involved in 2020 this year, that’s when you had all the media coverage, right? That’s when CNN was on the ground on. That’s when we were actually talking about it. But as soon as it became peaceful, then suddenly there was much less discussion, at least in the popular press. The same exact thing happened with Stonewall because there just happened to be reporters there because The New York Times happened to report on it. It sent a signal to the rest of the movement, and also to queer folks who were in other movements, including the anti war movement, including the black freedom movement, including women’s liberation that at last this other part of their identity was coalescing into a tangible visible movement. And so that’s why it exploded in size, even though activism and the ideology of the movement had long been established.

[0:24:40 Peniel] I want to talk to you about the chapter, the liberation, which is one of the last chapters. And there I thought you did a great job of showing a few things, and you do this in the chapter, the riots as well. But for those of us who grew up in New York City like myself in the eighties, the Village Voice was a very pro gay newspaper on. Do you really show the village voice before that village voice that doesn’t want to use the word gay or homosexual? And you say it’s right here on page 3 17, you say, quote its coverage of the in air in quotes again. Dyke and faggot riots, moreover, continued to infuriate the homosexuals. I was really struck by that. I was struck by how a paper that when I grew up in New York City, absolutely one of my first really thoughtful explorations of understanding gay identity, including black gay identity, was through the village voice and being able to read about very thoughtful essays and pieces and interviews. And yet, in the context of the 19 sixties, I’ve found it extraordinary that the voice was was home a phobic and and really despicable. And it’s true gay people. Oh, sure.

[0:25:56 Eric] But on the other hand, they covered it, right. They so, yes, they were using this this despicable, despicable language. But most outlets, most media, either publications or news cover. It was a conspiracy of silence, right in their minds, they just didn’t want to even touch this issue. So in a way, yes, it was offensive. But the fact that you know, immediately after a stonewall, the voice gave, you know, two very large, extensive articles to this A moment, uh, showed I think it showed to the gay activists that finally there was there was interest in what they were doing, but it also showed them that they really needed to educate the paper. And what people? I’m glad you mentioned that about that last, uh, night of riots is people don’t realize the riots lasted four different nights over the course of six days in the very last night was on a Wednesday night after a weekend of protests, because off the language that was used in the village voice on because the voice, you know, considered itself a ah progressive paper when they picketed outside the publisher’s office is, uh, they actually came and talked to him and said, Okay, we’ll stop using these offensive words, which I think says a lot, you know, that they actually were willing to change, whereas, you know, these other papers won’t give thes activists the time of day. Um, but it just goes to show how ingrained even in a supposedly progressive paper, the rhetoric and the homophobia really waas because I even in the Stonewall articles, which I encourage anyone to go look, all of the village voice is digitized and you can look at their old archives. And if you look at their coverage from July 1969 you can see, like, just as you said the offensive words but also things like, Oh, you know, at this moment the first you know, object was thrown in limp wrists were for gotten things like that, and it’s just it’s It’s somewhat amusing, but also a

[0:28:06 Peniel] little depressing. I want you to talk about comedy and gay is good and, you know, in the chapter of The Pride, which is the next to last chapter, the notion of pride in the many meetings of this work because you really introduce it even in the first few pages. But then, by the time we get to this sort of fulsome narrative of culmination I got, I had a deeper understanding of pride and, you know, sort of the many iterations of it and the multiple meanings of it. You know, pride is a metaphor for, you know, sexuality for citizenship, for dignity, so many different things. I want you toe talk about that because I think it’s so well done on how Kameni the gay is good is inspired by yes, black freedom struggles. But that notion of pride that even he might have had so many different folks who are queer who are trans have taken that and done their own iterations in ways that are, I think, truly profound, but at times can cause tensions within the movement as well.

[0:29:13 Eric] Yeah, and I’m so glad you use that word iteration because it’s, I think, the perfect word to show that, you know, you can have early versions of pride that are still maybe prototypes are still not fully developed but are just equally valid and that I think, you know, in my dissertation. And even in this book, I I think that one of the larger contributions I’m making to the study of history is most people assume that pride or gay power or declaring that homosexuality is morally good to say that gay is good, um, is an invention of the late sixties and indirectly rooted. And, you know, black is beautiful in, uh, Stokely Carmichael, and I argue that we actually need to be looking closer at Greensboro and 1961 the year after, when Frank Kameny and his Supreme Court petition the very first Supreme Court petition submitted by an openly gay man for for employment rights of homosexuals, he declares that homosexual activity is a moral good. And he does that because the federal government had told him that homosexual activity inherently was morally bad. So he was gonna prove that it was arbitrary and unconstitutional by making his own arbitrary argument. Because if he’s going to say that it’s morally good, then how is the government going to claim otherwise? Other than pointing to Scripture, which is, of course, unconstitutional. So I argue he’s doing the exact same thing that the students in Greensboro we’re doing right in reclaiming morality from themselves away from the white Southern segregationists quit long claim that, you know, the mixing of the races was immoral and they’re gonna lead to the destruction of society. And, uh, you know, had always held onto that that mantle of moral authority and the students proved them wrong. And they proved to the rest of the country they proved to Time magazine. They proved to the American public that, you know, they simply wanted to sit there at the Woolworth lunch counter and have lunch. And you see these white kids pouring catch up in Pepsi and, you know, acting despicably. How can you possibly believe that they are the immoral ones that these black students or the immoral ones it becomes so visually clear where the immorality lay? And I believe Frank Hammadi did that exact same thing as a legal argument in developing pride as as a strategy within his legal argumentation, which then grew over time, uh, to become more of a psychological antidote, an antidote to the feeling of inferiority uh, that, you know, black folks had felt equally just as much That same feeling, of course, more so. Going back way more in time because they were recognized as minority group. Whereas frank committee had to convince people that that gays were even a minority group to begin with. Um And so what did he do? He borrowed that same exact concept, and and xeroxed it went from Black is beautiful, too. Gay is good.

[0:32:24 Peniel] Who is Marsha P. Johnson? And can you discuss her relationship with Randy Wicker? It’s

[0:32:32 Eric] one of my favorite stories. And of course, it’s heartbreaking as well. Uh, Marsha P. Johnson was a black trans woman who was a sex worker. She was an activist. Um, she waas a figure within the community in New York City. Um, she was a veteran of stonewall. Uh, multiple eyewitness accounts. Have her there. Uh, there is one of my favorite accounts is she managed to climb a lamppost in a tight fitting dress and high heels and dropped a bag of bricks or rocks. We’re not quite sure what it was on to a police car below, which was one of the most I believe iconic moments of the entire Siris of uprisings. But she also teamed up with after Stonewall with Sylvia Rivera to create Star, which they called ST Transvestites for Action revolutionaries, which essentially was the country’s first homeless shelter for Queer Youth. And it created a new model for how we can help the most marginalized members of our own community. And she was in the in the nineties, friends with Randy Wicker, who is, of course, the activists who organized the first gay rights, uh, pick it and was really instrumental improving to him how misogynistic, how transphobic, how racist he had been in his early activism in the 19 sixties and using the strategy of respectability to exclude the most marginalized members of our community. And he realized how that strategy had been self defeating. And so now he’s still around. He’s living in New Jersey. He, uh, is has dedicated the rest of his life to fighting for in protecting, uh, trans women of color, in particular because Marsha in the nineties was was found dead, uh, in the Hudson. The police department, uh, immediately claimed that it was a suicide upon no evidence whatsoever of it being so uh, Randy and others, including Sylvia Rivera, were able to persuade them Thio, uh, Thio take away that classifications and eventually to reopen the case because, uh, there’s no reason to believe there was anything other than murder, which really speaks to a problem that continues in 2020. If you are a black trans woman, you’re 16 times more likely to be murdered. Um, and I think it shows, especially in light of the victories that we’ve had for, you know, sis white gay men like me, um, celebrating employment protections and gay marriage. Um, there are members of our community who are still at such high risk of violence. And I think now it’s time for us toe fight for them after having for gotten them consciously forgetting them for so long.

[0:35:39 Peniel] You end the book with a really poignant scene of frank committee at the White House several times. Um, on April 23rd, 2009, President Obama appoints the highest ranking gay official in American history John Barry, uh, to be the head of the office of Personal Personnel Management. Um, then in frank committee is 83 at the time he attends the swearing in ceremony. Two months later, he’s at the Oval Office. Uh uh, you know, looking over the president President Obama’s shoulder as he expands health care for for partners of gay federal employees. And finally, on June 24th, 2009, uh, Jon Barry gives him an official letter apologizing for what has said this shameful action. The United States Civil Service Commission in 1957 upheld your dismissal from your job solely on the basis of your sexual orientation. I thought that was you know, so movie. Um, you know, says with fervent passion of a true patriot, you did not resign yourself to your fate or quietly endure this wrong with courage and strength. You fought back. And what is what does Frank Kameny say?

[0:37:02 Eric] He stands and is very. He was not known for for brevity and anything he said. But in this one instance, he stood and simply said, Apology accepted. Yeah,

[0:37:13 Peniel] yeah, And so you talk about, you know, the don’t ask, don’t tell. Finally being ended by President Obama in 2010, but very poignantly you end with the July 21st, 2011 space shuttle Atlantis landing, and why was that so important in terms of Frank Kamani and NASA and his dreams?

[0:37:35 Eric] Well, I always tell everyone, you know, Frank Kameny did not want to be the grandfather of the gay rights moving. He did not want to be a gay activist. He wanted to be an astronomer. He wanted to be an astronaut. Um, he was better position than anyone in the country to be one of the founding fathers of the American Man Space program. Um, he would have been one of the first employees of NASA. He probably as an Army veteran, uh, would have had a very high probability of actually traveling to space. And despite ah, life of continuing to apply for jobs within the government, hey was never allowed to to serve on toe, actually use his incredible intellect, toe help our space program. And in 2011, America retired the space shuttle in the very last, uh, space shuttle touched down, and he was alive for that. And he passed away just a couple months after that. Um, and I think it shows, you know, his life was was a tragic one. But of all people, I like to think at least thank God it happened to him. You know, thank God that if the tragedy were to happen to anyone, it happened to someone who was willing to fight back toe, live in poverty for the rest of his life. Uh, so that he could continue fighting the government and helping others in constructing what we now know is as pride.

[0:39:10 Peniel] And my final question is, how do you think the deviants war speaks to? This current moment of black lives? Matter protests, uh, for for for racial justice and social justice all around the country and all around the world. And especially since BLM has been led by black queer, feminist black trans women, so many different activists really intimately connected. Toa l g b t Q A movements. How does the deviance war? And I just kept thinking about the contemporary watershed historical moment while reading this. How does this connect with now?

[0:39:48 Eric] If there’s anything I hope people take away from the book, it’s that we borrowed and we meaning people like me, white cis, gay men. We borrowed the entirety of pride from the black Freedom movement and we have gay rights because of trans women of color and time and time again. You see it through the book and through all of history you see it a stone wall. You see it throughout the seventies and eighties. It’s those with the least to lose who are the first to fight back, but also the first to be for gotten. And that includes trans women of color, especially black trans women. And so I believe the book proves that people like me who are celebrating marriage and prosperity uh, in our own presidential candidate we have a moral obligation to be joining in the fight for black lives and to be declaring that black trans lives matter. Uh, because we have tangible rights because of these groups. And so not only is it a responsibility on a basic human decency level, Thio declare the sanctity of those lives. But we need to take a step further. We need to be on the front lines, a tease, demonstrations and calling for the arrest of the officers who killed uh, Briana. And it just shows how much more work we have to get have to dio

[0:41:11 Peniel] Alright, we’re gonna end it. There were ending on an optimistic note of really what this extraordinary historical time period means for all of us. We’ve been chatting with Eric Savini, who’s written really a wonderful book, a brilliant book, The Deviants War, which is a New York Times bestseller. The Homosexual versus the United States of America, which was really a panoramic history of Frank Kamani, the Machine Society, but really gay liberation. Um, in the post war period, you know, you get the 19 forties, the fifties, the sixties and seventies, all the way up into AIDS and the Obama administration, the AIDS Crisis and Obama administration. So this is really a wonderful contribution to history. Dr. Eric Savini is an award winning historian of LGBT Q Y. A Culture and Politics. Hey graduated summa cum laude from Harvard and received his PhD in history from the University of Cambridge, where he was a gate scholar. The Deviance War is his first book. In his podcast is the Deviance world. Andrea Lee. Please get this book. It’s a New York Times bestseller. I’m sure it’s going to be made into a movie documentary multiple iterations, and it’s really that good. So Eric Savini, thank you for joining us on race and democracy.

[0:42:32 Eric] Thank you so much for having me. And the one thing I wanted to say is I hope people will also by Stokely a life, because it’s in the end. Notes. You cannot tell Frank committees story without telling the story of Stokely Carmichael and other folks like Buyer Rustin. And so I hope I’m looking at Amazon right now. It says there’s only 16 left in stock, so I hope the 1st 16 listeners will buy both both books because they’re the perfect perfect accompaniment.

[0:42:57 Peniel] Thank you. Thanks for listening to this episode, and you can check out related content on Twitter at Peniel Joseph. That’s P E N I E L J O S E P H and our website csrd.lbj.utexas.edu and the Center for Study of Racing Democracies on Facebook as well. This podcast was recorded at the liberal Arts Development Studio at the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. Thank you