“Freedom Papers: Evidence of Emancipation” highlights examples of how enslaved people gained freedom before the Civil War in the American south. Through the purchase of bonds, travel to states where the right to freedom was inherent, and other methods, these people secured a fragile hold on their freedom and sometimes the freedom of their children as well.

Documents used in this exhibit cover an era from Spanish rule to the end of the Civil War, including petitions signed by Spanish Governors, survey maps, and emancipation papers for entire families. These personal, often complex, stories show how the legacy of enslavement permeates American history.

Dr. Maria Esther Hammack of The Ohio State University has utilized the Briscoe Center archives for years, first as a center Fellow in 2018-2019 and then throughout her subsequent research. Dr. Hammack found Silvia Hector Webber’s freedom papers during one of her research trips and now works with descendants of the Webber family to amplify Silvia’s story.

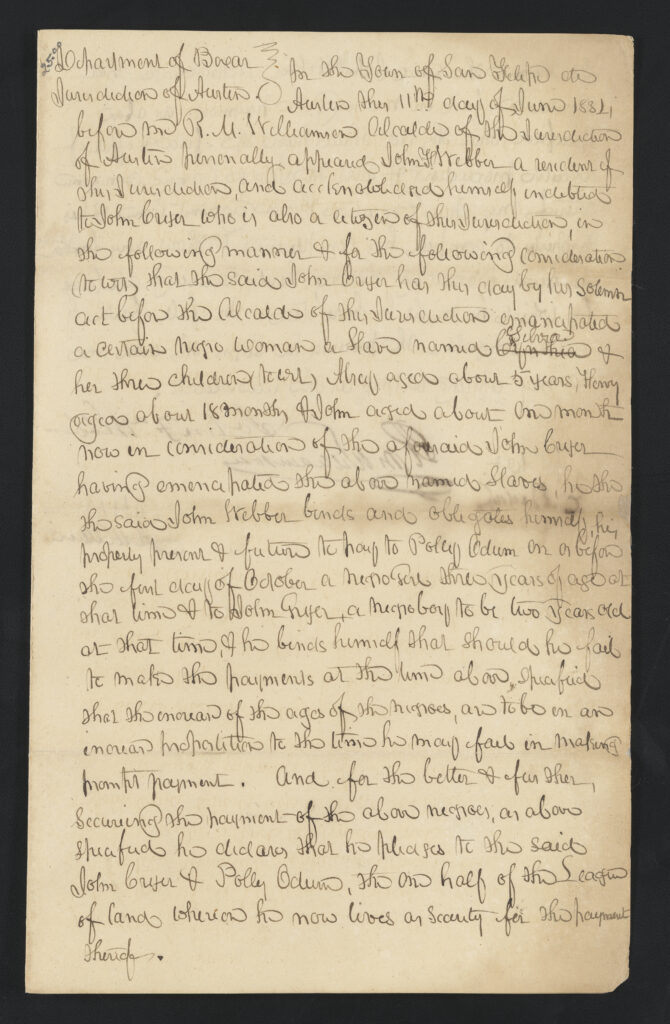

Silvia’s freedom, and that of her three children, was purchased in 1834 in a bond in the holdings of the Briscoe Center. Silvia Webber would go on to help others to freedom via travel to Mexico, and her house became a stop on the Underground Railroad. The Webber land, located east of Austin, gave its name to present-day Webberville.

We invite you to explore more evidence of this shared history through research in our archives and digital collections.

DEC Intro: This is American Rhapsody, a podcast of the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. American history is many things, but it’s most certainly a rhapsody, quilted together from the ragged patches of many disjointed stories yet somehow still managing to form a coherent whole.

I’m Don Carleton, executive director of the Briscoe Center, a repository for the raw materials of the past, the evidence of history that we collect, preserve, and make available for use. Each episode, we talk to the individuals who helped create that evidence, to the donors who preserved, and to the researchers who use those collections in their work.

And we keep the American Rhapsody going.

Hello, my name is Nathan Stevens, host of American Rhapsody. Today, we’re talking about our exhibit “Freedom Papers,” which displays documents that enslaved people used to gain their freedom before the Civil War. In today’s episode, we’ll focus on one story in particular. –that of Silvia Hector Webber, for whom Webberville near Austin, Texas is named. She was an unheralded part of the Underground Railroad, and her bravery was, in part, uncovered by one scholar researching at the Briscoe Center.

My name is Maria Esther Hammock. I am a Mexican scholar and public historian who does black liberation in North America,

Dr. Hammock’s journey and research began in a class at East Carolina University.

I had to take certain requirements and one of the those that were available was a class on the history of the old South. And I remember being very interested in the stories because the professor was talking about the Underground Railroad, and Harriet Tubman and abolitionism. Right. And I didn’t know a lot about the stories, but I didn’t know you know, being someone from Mexico, and going to school there. I knew that, you know, that Mexico had abolished slavery early on and that Vicente Guerrero has passed the decree in 1829. But beyond that, I really didn’t know a lot about these processes.

The professor that was teaching that class, his name is David Dennard. And I remember raising my hand and asking him, ooh, Can you tell me who the Harriet Tubman that that led people to Mexico was? And can you tell me how many people you know, went to Mexico to be free? And I remember he, you know, staring at me and saying, that’s a wonderful question, Maria, if you find out, please let me know. And every time that I pass by his office, he would ask me, “What have you found?” or every time I saw him. And so now I not only wanted to figure it out for myself, but there was somebody holding me accountable to find those stories or to find an answer. And that’s what led me to do this work for my master’s thesis.

And part of Maria’s thesis was dispelling myths around the underground railroad, so that more people could understand the details of how enslaved people escaped their bonds.

So in in the history of the United States, particularly in the stories of freedom that we are taught, it’s the stories of the Underground Railroad are stories that lead to Canadian destinations or north and spaces. So there’s a lot of emphasis on those movements of people trying to reach north in states where they can be they can be free, or Canadian spaces. And American in American history, the Underground Railroad means something very specific and, and through certain geographies that allows us to think of Canada or Canadian safe havens. Often we have made been made to believe that the Underground Railroad was this very strict process with conductors and officers and people are very much invested in this is we’re going from this place to this place to that place, these movements ebb and flow. There weren’t as a structure as we have been made to think.

But thanks to some help from Briscoe Center archivists, Dr. Hammock was able to sift through the collections to find what she was looking for.

The first person I met was Margaret Shlankey. And she I remember, you know, I was like, I didn’t really know how to ask for documents. I was like, I would like to see this and this and this. And she’s like, have you looked at the catalog? And I was like, I’m not sure. I don’t think so. And so she really did guide me to this is how you look for things here. And then she became that point of contact that allowed me to explain how to how to find things. Because of course, when I got there, I basically said, I’m looking for, for documents from runaway slaves to Mexico. So and that that initial trip, I actually found, I would say, two sets of document of bodies of documents. One was in the collections of Eugene Barker. He talked a lot about the slave trade through Texas. And what he did at the turn of the century is like the 1900s He sent out a lot of letters to elderly people are around different places in in the Texas Gulf Coast to inquire and ask if they remember a scene or witnessing the illegal slave trade. But some of those letters actually, that he received are like, oh, yeah, I remember that. On this date. There were, you know, a group of enslaved people brought in shackles and they were made to walk such distances. And on one of those replies, there was one individual, one man who wrote how some of the individuals were emaciated. And with him with the help of others, were able to feed them some fish. And it really gave me a different perspective to include that illegal slave trade through the Gulf. The other body of documents that I that I, that really did help were the Bexas archives, and you know, at the Briscoe Center, you had, you have both so you have the Bexar archives, the originals, and then you have the microfilm, right. And I remember when I first got there, I was directed to the microfilm and I remember inquiring, like, I know you have the primary documents, I want to see the sources themselves, you know, there’s nothing like looking at the, at the live, you know, documents. And one they have a wealth of information on escapees. So people who are leaving and escaping French and slavers in Louisiana and various parts of Louisiana and making it to Texas. So those are our calves, especially in starting like the mid 1700s all the way to the 18 I would say 1820s They have a rich body of documentation that highlights black mobility in those early in that early period.

And all of that led to discovering more information on the story of Silvia Hector Webber.

The way I came to her was very interesting the way I came to, to really consider Sylvia in my in the work that I was doing. I had I had applied for a Fulbright grant to Canada to do research in Canadian spaces. Because I was very, you know, I had done some of the research to reconsider, you know, Mexico in these processes. And in order for me to understand, you know, the underground railroad that led to Mexico, I needed to understand the underground railroad that led to Canada, but I reached out to the Fulbright director at UT. And to ask if there was a possibility that she could meet with me to prepare me for that interview. And she was very, very kind of very nice. she scheduled an appointment with me and like she said, you know, you’re doing fascinating work. And this makes me think about this woman that I don’t know if you’ve already done work on her found documents on her, but I think she needs to be part of your work. And I said, Who is it? And she said, Well, you know, this woman in Webberville and I was like, I had an idea of a woman from Webberville, right? But I didn’t have a name. And she said, Well, her name is Sylvia Hector. And then she told me the story what she had heard.

And she said, now, don’t ask me anything about it. Because I don’t know anything about her. All I know is what I’ve heard Dr. Freeman who spoke fluent Spanish, when she told me in Spanish, she said, But you know, “cuando el rio suena, agua lleva” …and that phrase utilized across Latin America, especially in Mexico to say, when something is if you hear something is there might be some truth to it, right? And so that’s what got me started on really trying to find more about Silvia and learning about her story, and centering her. And of course, the first things that I did was, you know, you Google things, Sylvia Hector, and nothing really was coming up at that time. But then when I realized, you know, Sylvia Hector and John Ferdinand, wherever, when I Googled John Ferdinand Webber, a lot of things came up particularly there were a lot of biographies on him, I ended up going to Webberville to look at the certain historical markers that they have, I would see John Ferdinand, whatever and references to his either she was referenced as his black wife, or his former slave, or as you know, but never by her name. And that’s, that did bother me a lot. Because, you know, this was a woman that if she, you know, was part of this network, but even if she wasn’t, if she was part of this, you know, foundational stories of free black individuals in Central Texas, I was really appalled by the fact that there were no biographies on her.

Despite the lack of information on Silvia, Dr. Hammock kept at her research at the Briscoe Center.

And so that following summer, I had the opportunity to do to work with the Texas State Historical Association with Jessica Ronasci . And she was very interested in having students draft biographies on women who shaped Texas history. And I remember one of the meetings with her, they had a list of potential women that one could write about. And I said, one of the biographies that I want to write about, it’s about this woman, Silvia Hector. And then I told her a little bit about the story. And she said, I think it’ll be wonderful. Do you think you can find things to write her biography? And I said, I’m not sure but I’ll try. And I had been a, I think it’s 2018 to 2019. I had been a Briscoe Center fellow. So I had in mind some of those archives. I remember I said, Okay, I’m gonna do one last look, and, and then I need to sit down and write it or figure out, you know, if I’m not going to be able to write it. And one of those folders that were at the end when I opened it, it was a it was a it was not cataloged as anything to do with Siliva, or anything to do with the underground rail or certainly not. It was the freedom papers. And I was like, What is this and that’s, that’s where I came to the freedom papers.

Silvia’s story connects to other collections and the current exhibit on display at the Briscoe Center. Silvia’s papers were in the Vandale collection, a vital piece of the Briscoe Center’s holdings on Texas history that’s been in the archives since the 1940s. Portions of the collection, from oilman and history collector Earl Vandale, reveal a stunning portrait of Texas as it warred against Mexico and became its own independent state. And the history of enslaved people is deeply intwined with the story of Texas.

So if I were to describe to someone the story of Silvia, I would say that I would situate her as a freedom fighter, one of the countless, if not 1000s, of black women who shape the stories of freedom and freedom processes in across the United States. And more, you know, in in more detail, I will also you know, talk about her story, how she went from slavery to freedom, and how she was very active in not only securing her freedom she had an active part in, in conceiving those freedom papers. Freedom for herself was not the goal. Freedom for her three children was also the goal right through those records, you won’t you’re allowed to see a glimpse of her was a foundational actor that shape Texas history that needs to be recognized more fully. I think she should be situated in alongside the names of Harriet Tubman. And you know, Silvia was born, enslaved in In Louisiana, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, she was separated from her mother at eight years old. And she was, you know, brought to what was then it was Missouri territory, the county of Clark that later became part of, of Arkansas. But you came to Texas in 1826. You know, with other with slaveholders that ended up being part of that body of individuals who moved to Mexican Texas, to start new lives. And by 1834, she had secured her freedom and the freedom of her three children. They had their own regulations and such that made it difficult for enslaved people to claim their freedom, even when they were in Mexican territory. And they could have claimed their freedom after 1829 and in some ways, but you know, this was a woman who made it her business in freedom to continue assisting others, and you see it on the records where many people who knew her like Noah Smithwick situate her as someone who was always kind and open to to assist anyone who came to her door, nobody came to her ranch and got turned away.

Silvia’s work as part of the Underground Railroad was already exceptionally dangerous, but it became even more perilous in the years leading up to the Civil War.

And you start seeing you know, her, of course, with a with the aid of, of John Ferdinand Webber leading people to freedom along the Colorado River. You know, if if you go to wherever bill, and of course, you know, at that moment, being someone who offered assistance to to particularly enslaved people was not okay, in especially after 1836, when Texas became the Republic of Texas, and the institution of slavery was very much part of that new Republic of Texas. She faced records show that they faced a lot of threats, they received a lot of death threats. And they made it very difficult for them to remain in Central Texas. There were a lot of factors that prompted them to uproot and leave in the 1850s. But importantly, the fact that they ended up having to forfeit their land that Weberville to pay off the debt that was incurred through the securing of the freedom of Sylvia and Sylvia’s children. And that moved them, you know, that moved them to Etawah county closer to the border, where they again established their ranch, licensed fairies and continue doing the work that they were doing in Central Texas. They were labeling Sylvia’s children as unionists, a couple of them ended up being caught and taken to jail, but later escaping, and so you start seeing the record that this was a family very much involved in the processes of freedom in assisting others, and of course, getting threats for that. And then at that moment in the stirring Civil War, that’s when Silvia ended up removing from herself from US territory and moving herself to Mexico to await the end of the Civil War. And she took some of her children they were, I think some of the younger children ended up going with her. And she stayed in Mexico until the 1870s, when she did return in the mid 1870s, back to the Webber ranch, and that’s where she lived the rest of her life.

For Dr. Hammock, her work wasn’t just about uncovering this history, but also making sure that Silvia’s bravery isn’t forgotten, and that her example can be a shining light in the modern era.

I think this is a story that is foundational to Texas history, but also to the histories of the border. What I like to say of the border lands and water, because it shaped this this Brittany is shared stories of slavery and freedom that are very, that very much connect the United States and Mexico. And I think the story Her story is very important to be civilized, because only when it is the civilized and when we highlight those undertakings, do we start to better understand this movement across this frontier as you know today we are very aware of what is going on with border crossings leading the other way right you know people reaching the US Mexico border trying to reach into the United States to for better future. Right. But less than 200 years ago, people were traveling the other way, trying to reach better futures in Mexican spaces, and I think there’s a lot to learn with that, to, to, if not allow us to, to produce answers to the issues that we have today at least allows us to, to better understand some of these processes in the context of slavery and freedom, and how relevant those stories are to, to border crossing stuff today. But I think the most important factor of why the stories are important to be civilized, is I think that in terms of anti blackness and race, civilization and racism, sometimes, you know, we may think that this is a problem that the that we are facing in the United States, but that’s also definitely a problem that we are facing in Mexico. So these are also shared issues that connect our past and I think that if we understand those, those stories and what they could mean for all of us today, we can be conceived better futures in which anti blackness is challenged and hope you know, in my in my optimist hopes, eradicated.

The Freedom Papers are on display now at the Briscoe Center at 2300 Red River in Austin, Texas. The physical exhibit will be up until June 28th. And the online portion is available at briscoecenter.org.